FREE RADICAL:

HOW ELIZABETH HAWES TOOK FASHION OUT OF BOUNDS

In 1941, American author and fashion designer Elizabeth Hawes was asked to create a wedding dress. Silk was rationed for the war effort, so she purchased a multitude of silk flags to make the skirt. The garment had a political message; Hawes placed the Axis powers flag (Germany, Italy, Japan) at the back, so the wearer would sit on it.

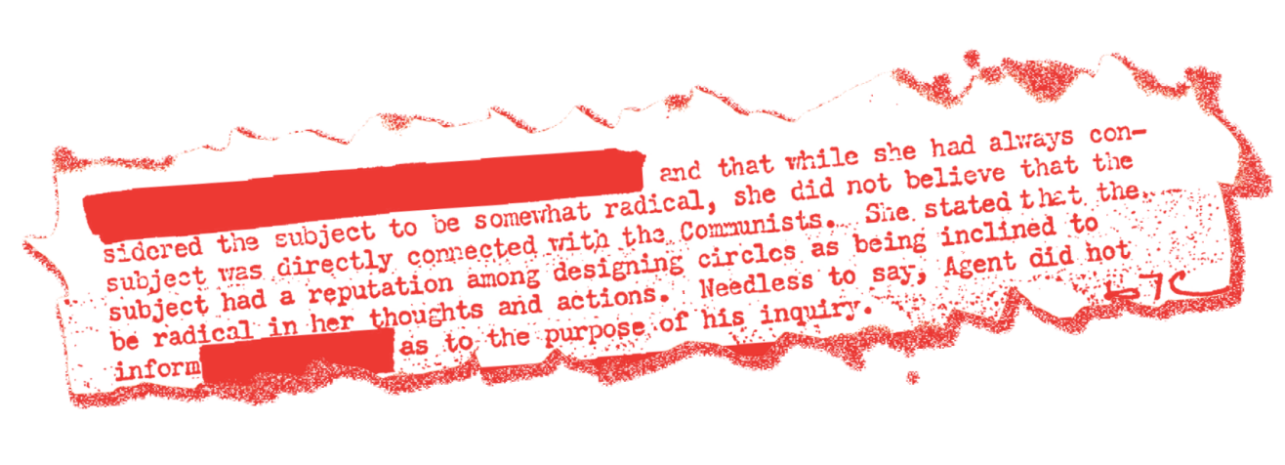

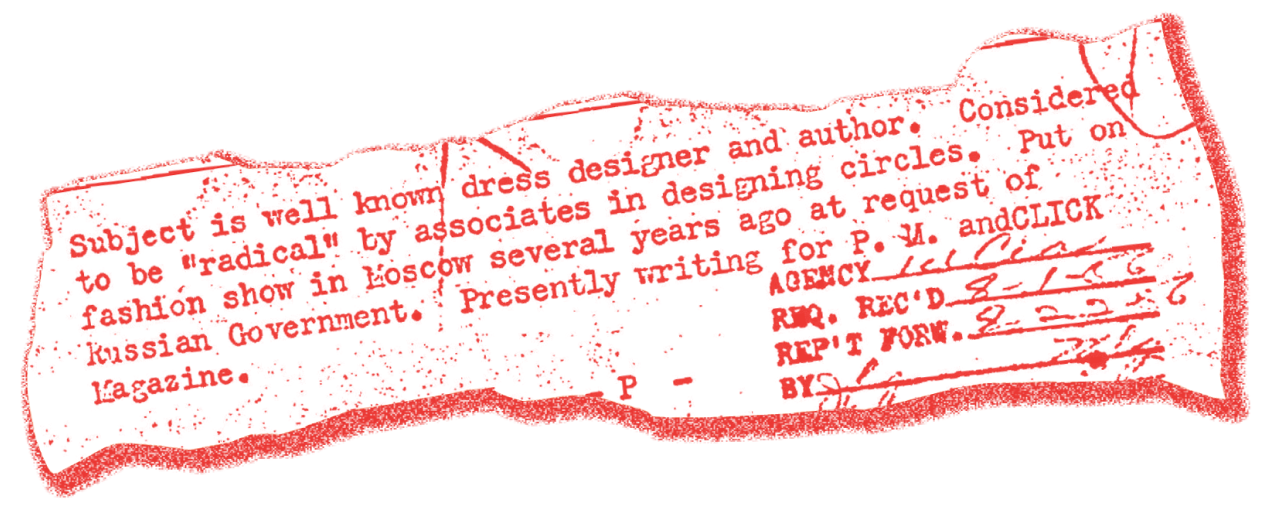

Throughout her life, Hawes (1903–71) pushed back against every possible convention with defiant wit. Her attitude was daring for the time, and the FBI investigated her for leftist activism. Hawes was “not believed to be directly connected with the Communists,” an entry in her FBI file reads, “but inclined to be radical in her thoughts and actions.”

She may have been America’s most anti-fashion fashion designer. In the first and best-known of her nine books, the screed Fashion Is Spinach (1938), she writes, “Fashion is that horrid little man with the evil eye who tells you that your last winter’s coat may be in perfect physical condition, but you can’t wear it … because it has a belt and this year ‘we are not showing belts.’” The industry’s wastefulness, sexism, and wage inequality triggered her fury.

Hawes “was all about personal style over fashion,” says Maria Ferrara, MA ’24. Ferrara served as the media manager for Elizabeth Hawes: Along Her Own Lines, the first contemporary exhibition about the designer, organized by graduate students from the Fashion and Textile Studies MA program and held in March in The Museum at FIT. “I’m a maker of style, not a fashion-monger,” Hawes told one interviewer. “Style is a comparatively permanent quality.”

A Vassar grad, she spent the first phase of her career in Paris, illegally copying couture gowns (and publishing fashion-related riffs in The New Yorker under the pseudonym “Parisite”). Back in New York, she started her own house on 56th Street. Movie stars like Katharine Hepburn and members of the intellectual avant garde were clients. Despite her egalitarian principles, her clothes were seldom within the budget of ordinary Americans. Hawes bristled at the compromises of mass manufacturing. “She felt that a dinner jacket should be an expression of something, not a reproduction of a uniform,” her son, Gavrik Losey, said.

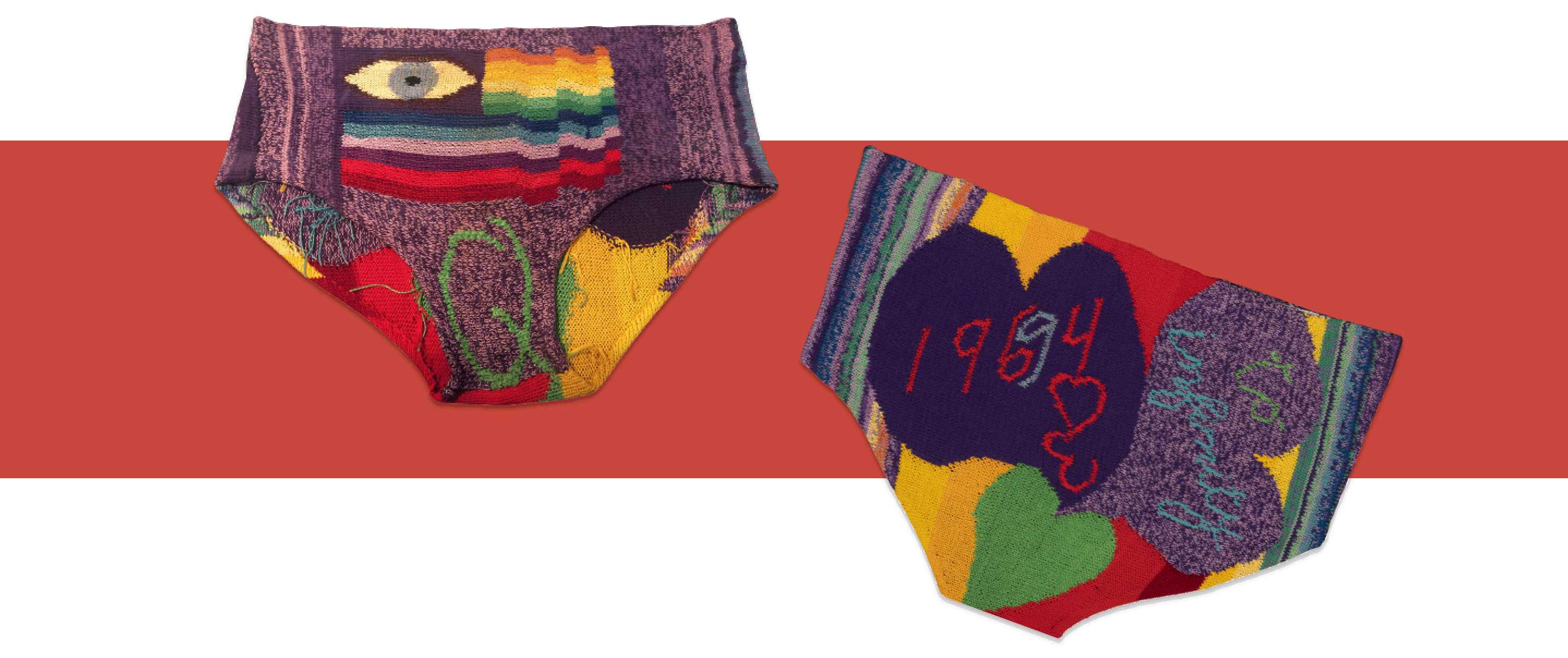

Inspired by artist friends Joan Miró and Isamu Noguchi, Hawes gave her outfits titles: “Curiouser and Curiouser” and “Beautiful Soup” (both references to Alice in Wonderland). Twice-divorced, she named a multicolored dress in silk and wool “Alimony.” It came with a black suede handbag made to look like male genitals. Another dress, “The Tarts,” featured arrows pointing at the bust and posterior. She had a descented pet skunk, which models walked on a leash during her fashion presentations.

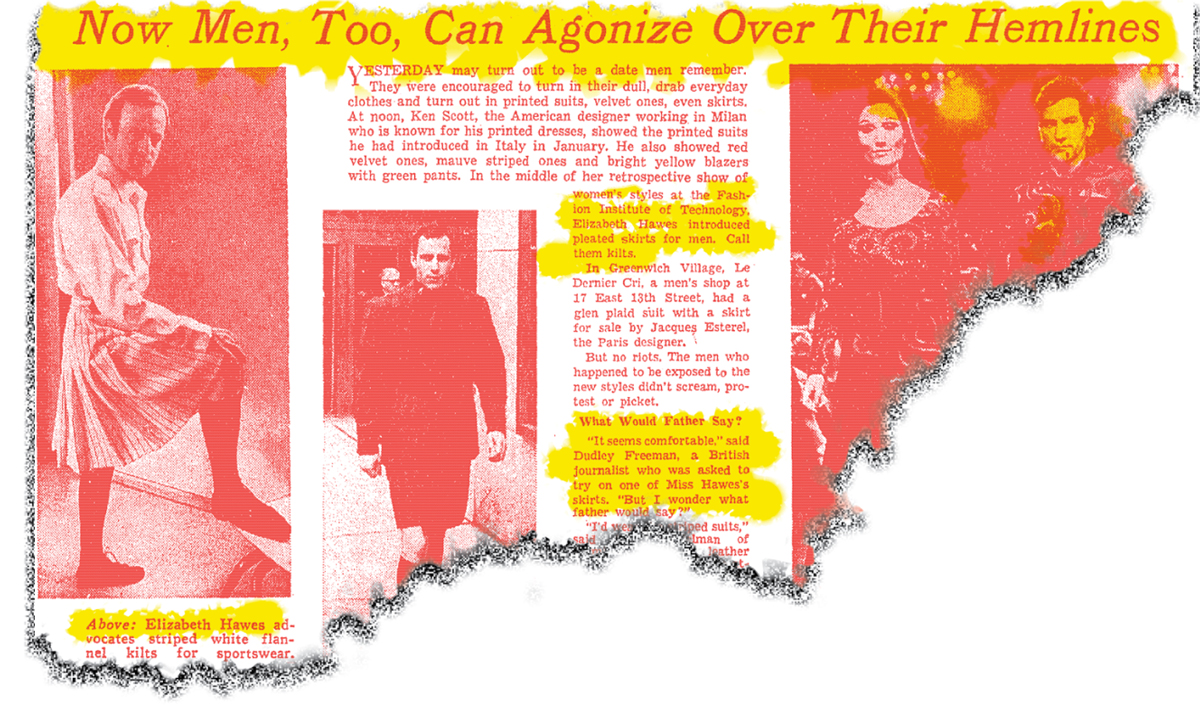

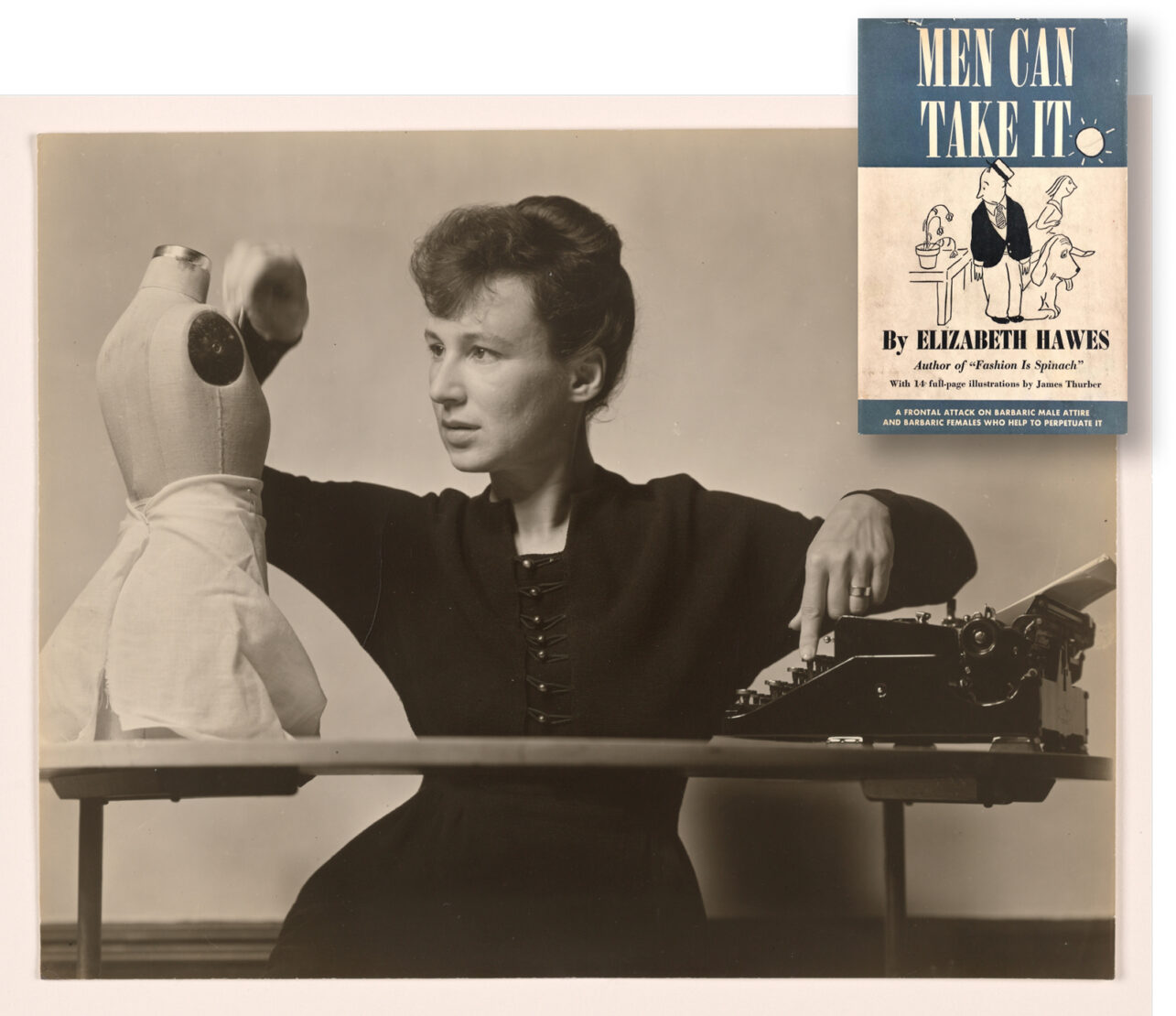

In an unpublished manuscript held in FIT’s Special Collections, Hawes wrote that she wore blue jeans to marry her second husband in 1937: “The justice of the peace asked, ‘Do you take this man to be your wife?’” She always quailed at gender conventions for clothing. “God help the American male with his background of having to be Masculine,” she writes in “Men Might Like Skirts,” a chapter in her first book. Her second, Men Can Take It (1939), enlarges this theme. Bewildered by the dull colors and uncomfortable collars in men’s fashion, she concludes, “Men are afraid of being thought ‘pansies.’”

“There’s nothing new about the idea [of men in skirts],” she told The New York Times. “The Moroccans, the Arabs, and the Greeks have been at it for years, not to mention the Scots. The only time men blanch is when you call it a skirt. If you say kilt, it’s all right.”

During the war, Hawes closed her shop and took a job in Michigan as the first woman to head the educational arm of the United Auto Workers. Ferrara says that in doing so, Hawes missed an opportunity to shine as other American designers did while Europe’s great fashion houses were shut. Perhaps as a result, she remains relatively obscure, though her son has another theory. “Because of her left-wing background, the FBI wanted to sabotage her and told her clients that she was … dangerous, so they left her,” Losey said.

Hawes first came to the FBI’s notice because she held a fashion show in Moscow in 1935. Little information about that groundbreaking presentation appears in her FBI file. A column she penned in 1942 for the Detroit Free Press, however, is quoted at length: “Four million Negroes, male and female, as well as six million white Southerners, are deprived of the right to vote because they cannot pay the poll tax,” she wrote. “I think we can all agree that the United States is not a democratic country.”

As a writer, activist, and feminist, Hawes remains exemplary: a fashion visionary whose irreverent verve and progressive bent are still relevant.

Visit the online version of the Hawes MFIT show: https://fitnyc.pub/hawes