by Raquel Laneri

When Melissa Marra-Alvarez ’04 and Elizabeth Way, curators at The Museum at FIT, started working on the exhibition Head to Toe, which examines 200 years of women’s fashion accessories, they wouldn’t have thought to include face masks.

That was last summer, before COVID-19 hit. By late March of this year, many states were requiring citizens to wear face coverings in public to help curb the spread of the virus, which had already ravaged other parts of the globe. It didn’t take long for people to adopt them not only as protection, but as fashion.

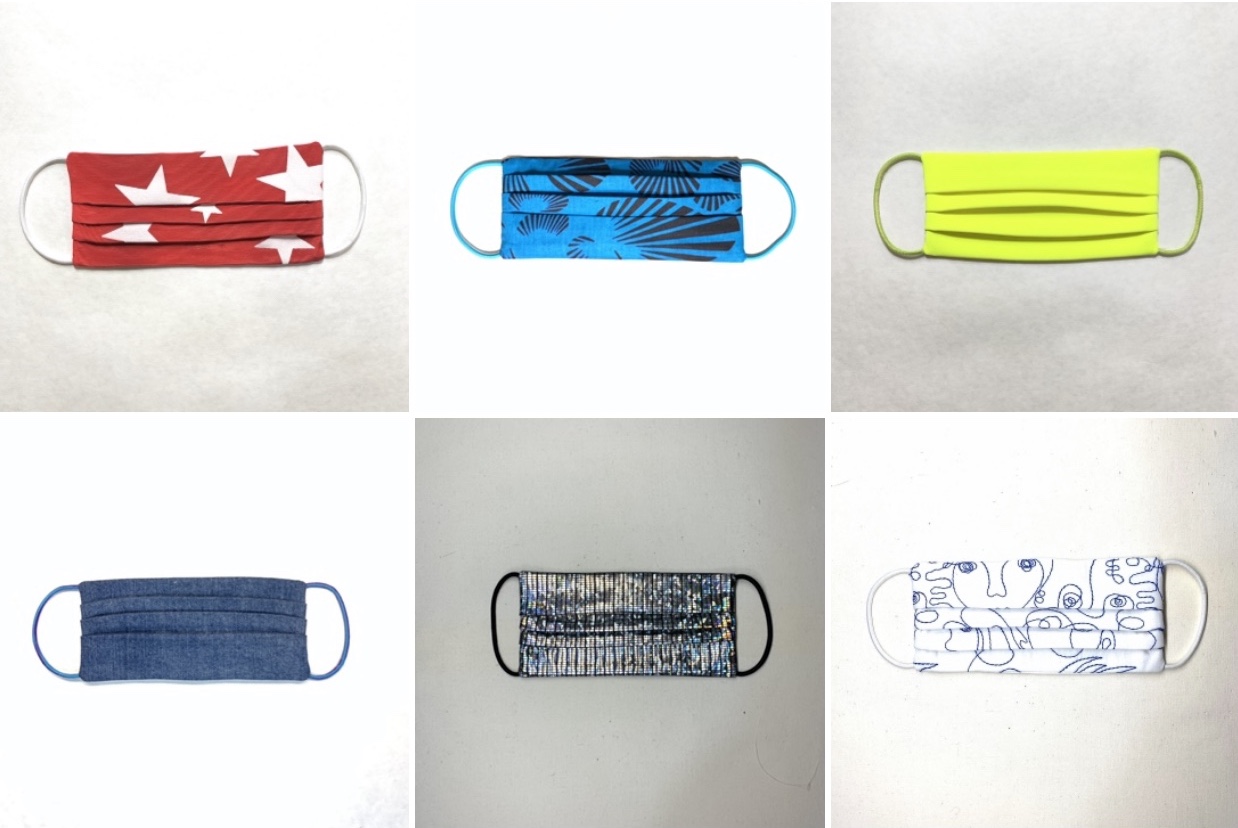

Now, designers are increasingly offering masks in an array of colors, prints, and styles: from florals to camo, from rich to retro to post-apocalyptic.

“I absolutely think you are going to see masks more in high fashion,” says designer and Fashion Design instructor Michael Kaye ’89, whose luxe handmade versions feature bold Liberty of London prints.

“I have the feeling that the Chanel tweed suit will have a Chanel tweed mouth covering with it,” Kaye predicts, “or there will be a Prada mask with the triangular logo as the mouthpiece that you breathe through, filtering the air.”

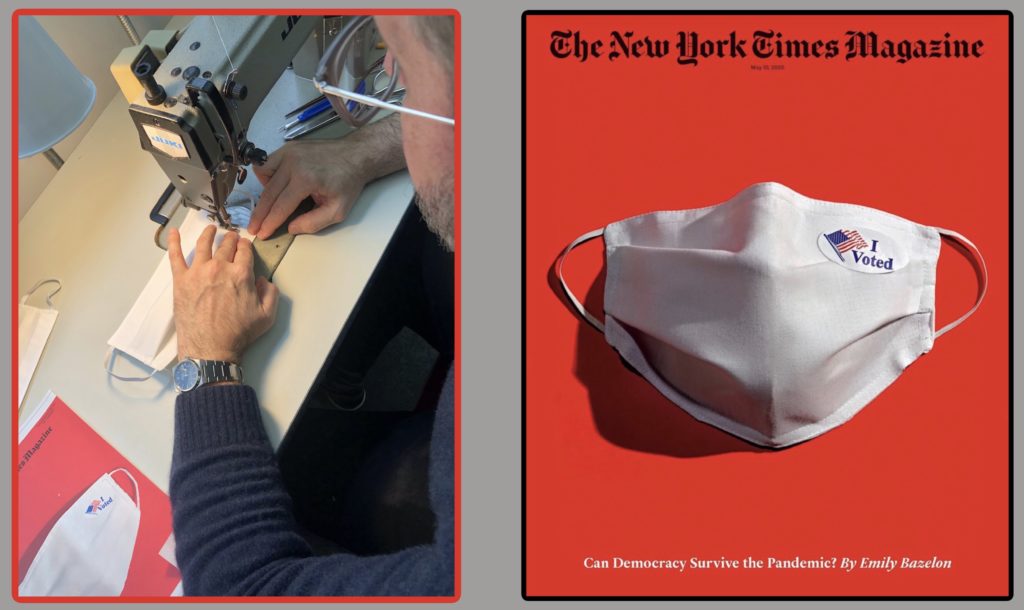

After the pandemic hit, Marra-Alvarez and Way decided to include a mask in Head to Toe, whose May opening has been postponed due to the virus. Masks—like sunglasses and parasols, which were originally conceived for protective purposes—“have quickly become expressive and fashionable among the general public,” the curators wrote in an email. And like many other stylish accoutrements, masks are far more than meets the eye.

“In the current moment, face masks have become particularly potent accessories that represent important social issues,” they added. For example: “Ideas of contagion and protection, as well as social responsibility.”

Watch: A Hue video about masks as fashion.

Face coverings have long been used during times of crisis, both as protection and as a symbol. During the plague in the 1600s, doctors wore leather masks with pointed beaks stuffed with incense, since people mistakenly believed the plague was transmitted through smells. (As The Museum at FIT Director Valerie Steele told Fast Company, “They were terrifying to look at and expressed the horror that that society was experiencing.”)

In the late 19th century, scientists began to learn more about germs and how they spread, and surgeons began wearing masks during procedures to protect patients. Women in the streets of Paris wore lace veils to protect themselves from dust particles. During the so-called Spanish Flu outbreak, from 1918 to 1919, officials convinced Americans to comply with mask-wearing ordinances by saying it was their patriotic duty to protect one another and the troops as they fought World War I.

The Second World War brought a whole other set of dangers, and Europeans often carried gas masks, in case of an aerial bombing. According to Ellen Lynch, professor in the Footwear and Accessories Design Department, luxury brands like Hermès found inspiration and profit in these new, often government-issued head-coverings.

“It gave the accessory industry an opportunity to create bags that these masks were held in, which was a boon for the handbag industry,” she says. These rectangular bags also sparked a trend that would far outlast the war. “Of course, the box bag after a while became a regular fashion statement,” Lynch adds. “And now they come in a variety of shapes.”

-

Precautions taken in Seattle during the Spanish Influenza Epidemic would not permit anyone to ride on the street cars without wearing a mask. About 260,000 of these were made in three days by the Seattle chapter of the Red Cross, which consisted of 120 workers.

Westerners kept the bags but have been slow to embrace face coverings as fashion, unlike in East Asia, where it’s not uncommon to see hip young people donning “edgy” or “cute” masks as part of a coordinated look—at Tokyofashion.com, many “Harajuku boys” and “Lolitas” model the accessory. It has infiltrated high fashion there too: The Museum at FIT owns an ensemble by Shanghai-based designer Masha Ma that includes a delicate floral face mask. Still, it’s hard to shed those connotations of disease and death in the U.S.—partly because previous recent epidemics, such as SARS and MERS, didn’t affect the West as much as it did parts of Asia, and partly because the collective, public-good ethos behind mask-wearing in the East doesn’t quite mesh with the individualism so prized in America.

Yet that attitude is changing—and designers are leading the charge, helping “normalize” mask-wearing by creating beautiful, functional masks that people will actually want to wear.

Alumni Pivot Their Focus to Masks

“I remember the first time I wore a face mask back in March, and I was startled by how humbling the experience was,” Daniel Vosovic, Fashion Design ’05, recalls. “I felt unnerved wearing it, I felt that I unnerved others around me. No one could see my smile or my personality. It was like all anyone could see was M-A-S-K coming at them.”

That’s why Vosovic started manufacturing masks for his made-to-order label The Kit. These cotton coverings feature bright flowers, beach scenes, and vibrant colors. The Kit offers five masks for $50, with all profits going directly to a COVID-19 relief fund. Vosovic says that the fund has raised more than $10,000 so far.

“I am very much a believer in being the bright spot,” Vosovic says. “There is something powerful about the fact that through color and print, you can not only change your own outlook but the outlook of those around you. Being the bright spot, even in dark cloudy times, can make a world of difference.”

Designer Chloe Dao, Patternmaking Technology ’94, says that selling masks is a way to keep her business going at a time when people are buying less and shops and boutiques are closing. The Houston designer initially began making masks out of scraps of fabric to give to medical and essential workers, asking her Instagram followers for donations. “Then I got this email, saying, ‘I would love to donate, but I want to be guaranteed a mask,’ and I was like, ‘Oh, maybe I should sell these.’ Bills were coming up, I had run out of fabric and had to buy more, I was still paying my employees, so I was like, ‘I need to be realistic about this.’”

Now, the Season 2 Project Runway winner sells masks in several patterns in cotton or an antibacterial neoprene for between $12 and $25. The funds enable Dao to avoid losing money while providing masks to homeless shelters, medical workers, and more. She says she’s donated 4,000 masks so far.

Kaye says that despite using expensive fabrics, he feels that he can’t charge more than $10 for one of his signature creations. “The price covers the [cost of production] and my time,” he says. “I don’t want to price gouge—I see this as paying it forward.”

The designer initially wanted to donate masks to hospitals, using a pattern from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “I had a box full of Liberty of London fabrics under my table, and I made 50 of them,” he says. “Then the edicts came out that hospitals did not want homemade masks.”

Kaye instead distributed the swanky masks to neighbors and friends. “My partner walks the dog in Central Park with a whole litany of Park Avenue ladies, and they all started wearing them. Soon I was getting all these orders from the Upper East Side.”

Since then he’s made more than 1,000 masks, and has expanded his offerings to include children’s sizes (in fun cartoon prints). He has 101 different prints to choose from, ranging from art nouveau swirls to elegant butterflies to tough tartans.

And the high-end designer, who has gowns in FIT’s and the Met’s collections, treats mask-making as seriously as his couture.

“This isn’t a short-term thing,” Kaye says. “The world is going to have to be wearing masks, and it might be for a while. It could be forever. So I try to make them as extremely beautiful as I can.”

As the pandemic continues, personal protective equipment, or PPE, has become a necessity both in and out of hospitals. Caroline Berti and Karen Sabag, both Fashion Design ’07, founded Sew4Lives, a national network of volunteers organized to sew hospital-grade masks, and supplied thousands of these urgently needed masks in the early months of the pandemic. (Read more here.)

Though specialized facilities are required to make the N95 masks needed for health care workers, many other FIT alumni are using their sewing skills to craft them for the public. These masks don’t necessarily protect the wearer, but might protect others from someone who’s carrying the virus, whether or not they have symptoms. Here are just a few examples.

Babi Ahluwalia, Textile Development and Marketing ’96, and Sachin Ahluwalia, Fashion Design ’96, are a husband-and-wife team known for their luxury label Sachin & Babi. To help protect frontline workers against COVID-19, they are launching The Good Kloth Company, which will provide gloves, masks, scrubs, and uniforms for medical and other industries that require them. The cloth will incorporate an antimicrobial coating that won’t wash off in the laundry. The PPE will debut later this year, and a consumer line is planned for 2021. Read more in Vogue India.

Alexander Andronescu, Fashion Design/Florence ’17 (left), produced 9,000 masks at cost for the Monrovia, California, school district in his small Los Angeles factory. He uses a moisture-wicking stretch fabric that feels good to wear. “A lot of companies aren’t gearing masks toward kids,” he says. “It’s important to make it comfortable for them.” He also makes reusable, washable gowns, and has donated masks and gowns to the San Marcos Treatment Center in Texas, St. Jude Heritage Medical Group in California, and Mount Sinai Hospital in New York.

Rosa Chavez, Fashion Design ’04, who teaches at the High School of Fashion Industries, started NYC Sews to produce masks for civilian use. She and her two co-founders built a network of tailors and fabric donors and secured a loft space large enough to permit social distancing. In its first week of production, NYC Sews made almost 1,000 masks—which will be donated to the Taxi and Limousine Commission.

Luis Peralta, Fashion Design ’15 (right), is a production coordinator for a designer in New York. When the lockdown began, his salary was reduced, so he and his mother supplemented their income by selling masks made with leftover fabrics from his custom design side business. He took apart existing masks to study their construction and designed a version that was protective, comfortable, and stylish. He donates additional masks to Fierce NYC, a charity helping homeless LGBTQ youth in the Bronx. Wendy Williams recently wore one of Peralta’s masks on her show.

Tara Lynn Scheidet, Fashion Design ’01, is known for her wedding gowns made from natural, organic, and repurposed fibers. In March, she pivoted to hospital gowns. Scheidet made a pattern with detailed instructions, and a nearby arts organization, Catamount Arts, offered its space as a makeshift factory. She coordinated fabric donations and led a team of volunteers to sew hundreds of gowns that were donated to a local hospital, to give patients a little bit of extra comfort.