by Jonathan Vatner

When FIT transitioned to remote learning in March, many courses had to be altered dramatically. Take, for example, PH 253: Traditional Photography. The fourth-semester course teaches students to use old-school cameras and develop film in a darkroom. Since analog cameras are rare these days, the faculty and students had to get creative.

Professor Ron Amato gave his students a six-week project called “In a Time of Social Distancing,” which required them to begin with an analog element, whether it be a film camera, a camera obscura, existing family photos, or magazine cutouts.

“I realized that a lot of the learning objectives could be fulfilled without the darkroom,” Amato says. “I thought, ‘How can we start out with an analog process and move it into a digital world?’”

Pressed to adapt, the students produced remarkable work.

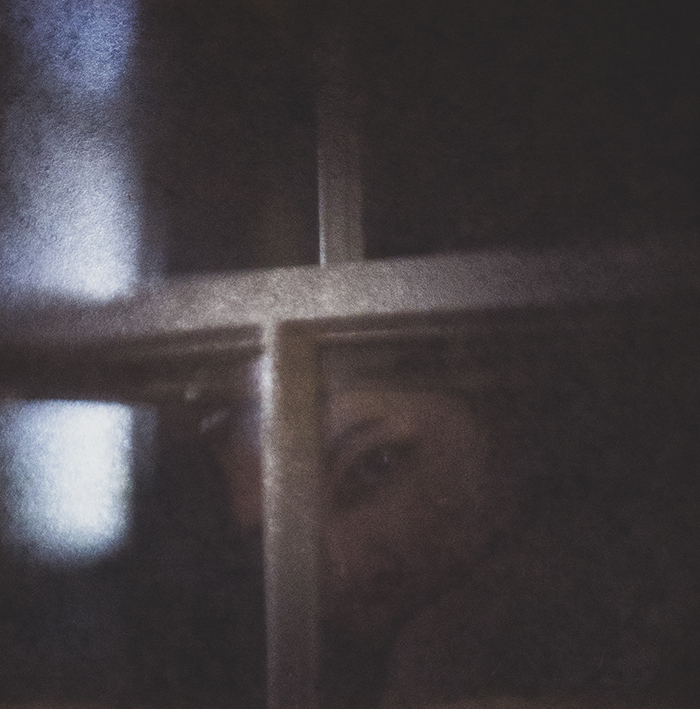

Danikah Chartier created a camera using a telescope lens, a mirror, and a cardboard box with a piece of wax paper to project the image onto. Then she used her digital camera to photograph the image that appeared on the paper. Her self-portraits using this method are spectral and moody, full of texture and mystery.

After her parents came down with COVID-19, Paula Villota became the de facto caretaker for the household. She left food outside her parents’ door and took care of her younger siblings. Using a Mamiya C330 (a twin lens reflex camera from the ’70s) and a bunch of expired 120 film, she made images that ache with loneliness.

“I made photographs of some of those dishes left outside their bedroom door to represent the painful distance we all had to endure,” Villota wrote in her statement.

Isabella Hanley covered her windows with black garbage bags and poked a hole in them to make a room-size camera obscura, in the vein of Abelardo Morell. She photographed her sister and some hanging flowers, with an image of the outdoors projected upside-down onto a tarp behind them. The images are subtly blurred because the exposures with this DIY camera lasted about 30 seconds.

About the project, she wrote, “This technique, while teaching me about the origins and the science behind photography, also opened my mind about how to use all the resources available to create meaningful art.”

Zachary Olewnicki made collages of photographic prints, much like David Hockney’s “joiners,” of his family at home wearing masks: his father playing solitaire, his mother coming home from her job at a hospital, his brother playing video games, and himself waking up. When placed against photographs of the empty rooms, his family seems fragmented and impermanent. “I couldn’t help but think how we basically became dolls at the hands of COVID-19,” he wrote, “which is why all rooms are shot … as if you were looking in from an opened doll house.”