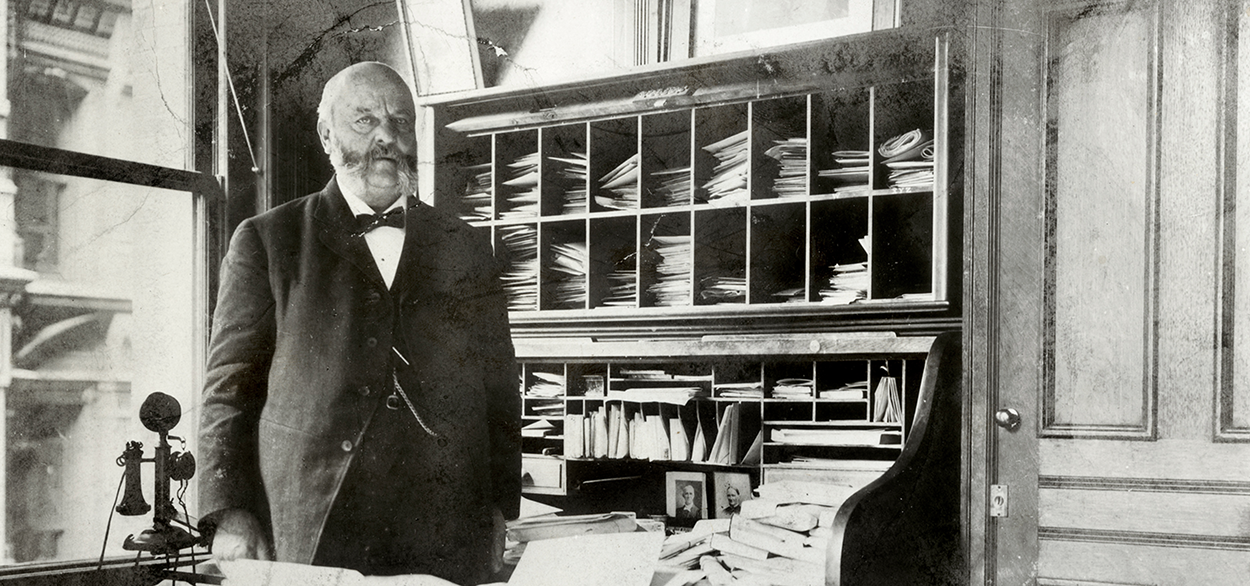

In the late 19th and early 20th century, no American embodied the crusade for Victorian morality better than Anthony Comstock (1844–1915). As a U.S. postal inspector, he enforced the notorious Comstock laws, which enabled the confiscation of any materials with sexual content sent through the mail.

In Lust on Trial: Censorship and the Rise of American Obscenity in the Age of Anthony Comstock (Columbia University Press, 2018), Amy Werbel, associate professor of History of Art, tells this story through the images and words Comstock spent his career trying to squelch.

In a front-page review in the prestigious Times Literary Supplement, noted literary critic Elaine Showalter called the book “a richly detailed, deeply researched … account” that is “lively and instructive.” The book, Werbel writes, is a “study of a battle against vice” that reveals the “boundary between free and suppressed culture, and the critical importance of ‘We the People’ in determining its place.”

Comstock’s youth shaped his expectations about what constituted proper art, Werbel writes. He grew up in the puritanical Congregational Church in New Canaan, Connecticut, where “art” usually meant didactic lithographs like this one depicting The Good Tree, a symbol of divine grace, which were displayed at home or in church.

Comstock came to New York in his 20s, after serving in the Civil War. He wanted to become the next A.T. Stewart, then the city’s most successful department store owner. In the late 1860s, leadership of New York’s Young Men’s Christian Association lobbied state legislators to write laws allowing for the arrest of people who created, distributed, or consumed sexual images. The YMCA’s main concern was imagery that could incite young men to lust and masturbation. For many Christians in this era, any sexual activity not devoted to procreation within marriage was sinful. Comstock shared this sensibility, as Werbel shows in excerpts from his diaries: “I debased myself in my own eyes today by my own weakness and sinfulness, was strongly tempted today, and oh! I yealded [sic] instead of fleeing to the ‘fountain’ of all my strength.” Struggling in the competitive world of New York retail, Comstock volunteered his services to the YMCA. With his involvement, it launched the infamous New York Society for the Suppression of Vice (NYSSV).

With assistance from the New York state legislature, and an alliance with the Post Office Department, the federal agency that deputized Comstock as its agent and censor, the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice opened an office near City Hall in Manhattan. Agents raided stores, warehouses, saloons, theaters, and art schools. For eight decades, they prosecuted, fined, and jailed thousands of Americans on obscenity charges.

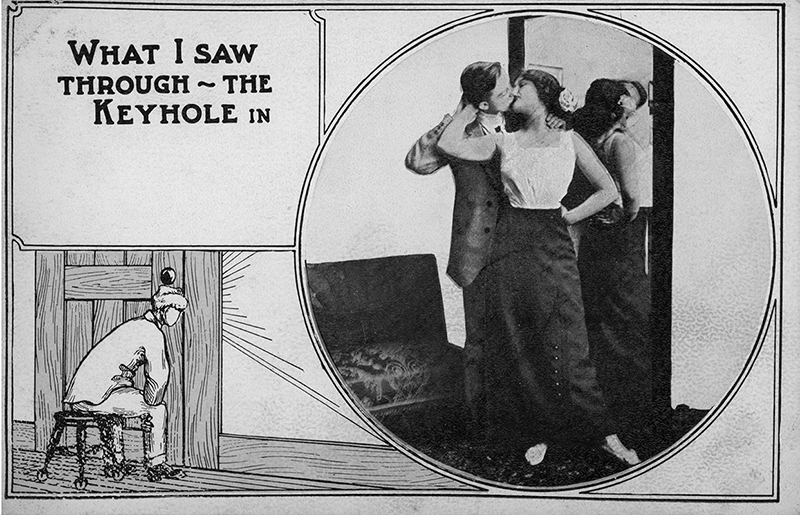

In 1877, Comstock investigated the Columbia Opera House at 12th Street and Greenwich Avenue, where impresario Jake Berry and his wife, Belle, staged burlesque shows featuring “naughty Parisian Dances.” A subsequent police raid led to the arrest of 28 performers, a highly publicized trial, and the conviction and imprisonment of Jake for running a “disorderly” business, defined as “open promiscuously to the public, and resorted to for the purposes of prostitution or indecency, or of corrupting, debasing, and depraving public morals.”

In the 1890s, living pictures, or tableaux vivants, became a popular form of entertainment. Actors posed in elaborately staged scenes, sometimes recreating legends. Five men and women were arrested during a tableau of the Orpheus and Euridice myth at New York’s Casino Theater. “Prosecutors may have been especially eager to shut the show down given that Euridice’s left breast was exposed in the show’s souvenir photograph,” Werbel writes. Artist William Merritt Chase, president of the Society of American Artists, testified for the defense, stating, “There is nothing immoral in the human frame.”

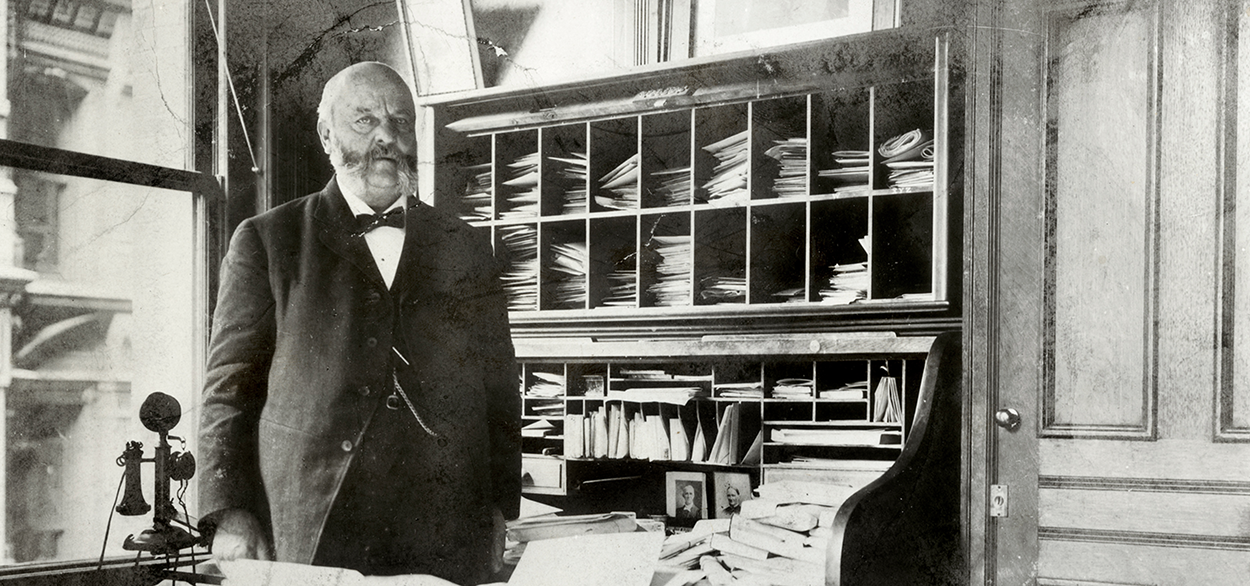

Comstock reached his peak in the first decade of his career, censoring purveyors of “racy magazines” and “dirty postcards.” Emboldened by his accomplishments, he moved on to people of higher social standing, such as the owners of saloons decorated with expensive European oil paintings (like William-Adolphe Bouguereau’s 1873 Nymphs and Satyr); and administrators of the Art Students League of New York, whose publications included reproduced student drawings of nude models. Werbel shows that Comstockery “worked” when directed at the middle and lower classes, who lacked political and social capital, but not when targeting its richest and most powerful citizens who were deemed to be impervious to “depraving influences.” As the Progressive Era took hold, free speech activists emerged who defended American liberties, including organizations of attorneys such as the National Defense Association and Free Speech League, both forerunners of the American Civil Liberties Union.

Comstock’s own hunger for the spotlight further undermined his effectiveness. He became an object of ridicule in the press, as in this 1906 cartoon, which shows Comstock forcing horses, dogs, and a cat to wear pants, while the sight of an ordinary garter sales display sends him reeling. Further, the more he denounced obscenity to the American public, the more people became aware of, and curious to see, the suppressed materials. Comstock died in 1915; the NYSSV, already much diminished in influence, continued to promote censorship until 1948, when the society finally closed, due to a lack of funds and political support. Today, one legacy of this era is that proponents of free speech have strategies for defending sexual expression. Kirkus, a leading book review magazine, aptly summarized Lust on Trial as an “incisive history of the futility of censorship,” a lesson that still resonates today.