by Jonathan Vatner

Lori Polson doesn’t paint for a living—the Advertising Design grad facilitates high-end portraiture by matching prestige clients to world-renowned artists. But she’s always loved painting, and when stay-at-home orders were instituted in March (and the portraiture business ground to a halt), she got out her brushes and began a series of portraits in oil of family and friends who were also stuck at home.

“The whole world shut down,” she says. “I thought, ‘When am I going to have this much time to paint again?’”

She says that when she shared these portraits on Facebook, the response was overwhelmingly positive. Some gave her commissions. The mayor of her borough, Woodcliff Lake, New Jersey, invited her to join the local council for the arts.

Her agenting business is picking up again—artists are painting from photographs and via videoconference—yet she maintains her painting practice.

“I didn’t know I could paint every day,” Polson says. “This time has opened up a whole new realization of what people are capable of.”

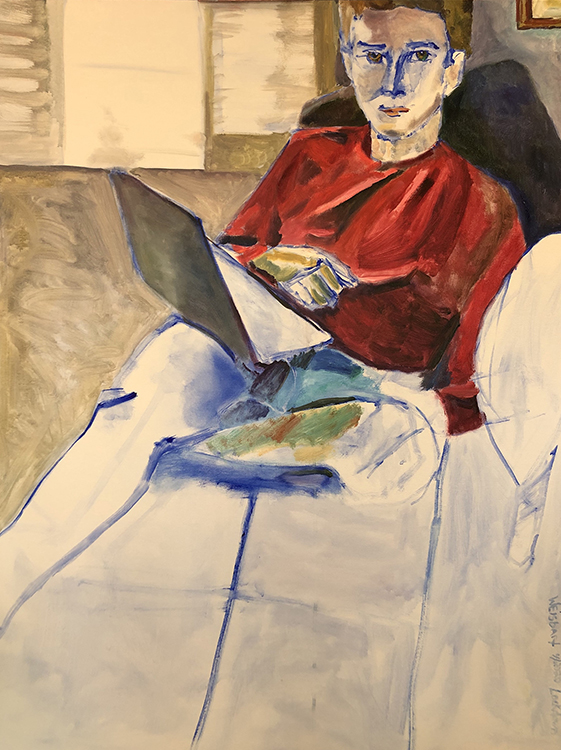

Polson’s teenage kids were glued to their devices, so she painted her daughter, Jessie, with her phone and her son, Ben, with his laptop. They reacted in opposite ways to becoming models for mom. “My daughter started screaming, ‘Don’t paint me! Don’t make it look like me!’ My son was like, ‘If you’re going to paint me, get my likeness better.”

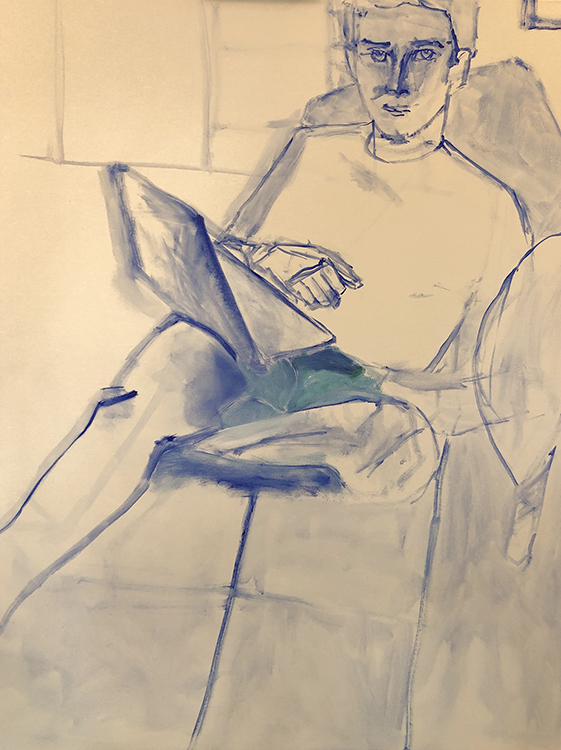

A side-by-side comparison of the initial sketch and the completed painting of Polson’s son.

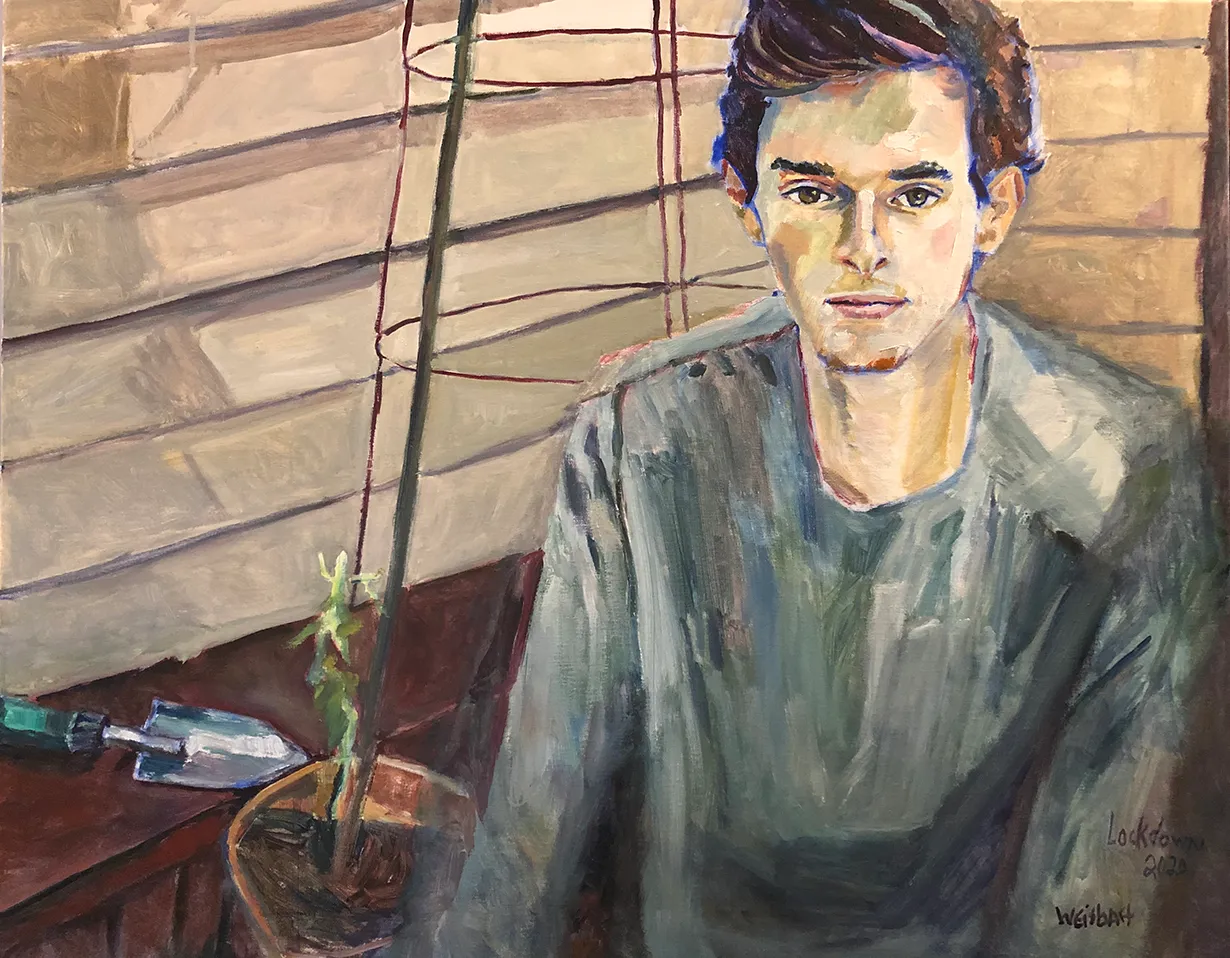

Polson painted two portraits of her son, one of him gardening—a hobby he took up after the pandemic began. “He became a maniac planter,” she says.

She also began making portraits of friends. In the past, she preferred her subjects to sit for her, but to maintain social distancing, she paints from photos of them doing typical shelter-in-place activities. Her boyfriend played Scrabble with Polson and her son, and a friend taught a yoga class on Zoom—close inspection reveals that the instructor is framed by a computer screen. Most of the portraits include windows to emphasize the frustration of having to stay inside.

The rotating images above reveal Polson’s process in painting her daughter.

Clockwise: Ben in the garden, Polson’s Scrabble companion, and a friend teaching yoga on Zoom.

When painting a kid trapped in a one-bedroom apartment with his mother and her boyfriend, she tried to communicate his frustration. She doesn’t usually paint smiles but made an exception for her friend’s daughter, feeling triumphant after running 21 miles on her 21st birthday.

Polson’s process begins with a mood. She looks into her subject’s eyes and tries to understand what they’re thinking and feeling, then considers how to communicate that emotion on the canvas. She paints the facial expression first, focusing more on personality than likeness. She fills the large canvases quickly, leaving her outline and brushstrokes visible, so the viewer can see her process and feel her energy.

Julia after her 21-mile birthday run, and Jack the baker making sourdough.

Lori Polson

If a painting isn’t done in a week, Polson becomes frustrated and can’t sleep. She works in a state of such intense concentration that she is afraid to look away even for an instant. “My husband feeds me cheese and crackers—he shoves the whole thing in my mouth,” she says. “If I get distracted, getting back to it is so difficult.”

Featured image [girl with mask]: Polson’s 15-year-old neighbor wanted to be shown wearing a mask in her bedroom—she’d just been given the handmade mask by a friend and found it beautiful.

The Portrait BrokerFor 15 years, Polson has been brokering high-profile assignments for portrait artists. She used to be an art director for advertising agencies like Saatchi & Saatchi, but she found the long hours incompatible with raising kids. From the many painting classes she’d taken at the Art Students League, she knew painters who’d gone on to become world-class portrait artists. She realized that if she represented them, she could work from home.

Artist representation is rarely an exclusive arrangement, so she was able to assemble a stable of artists who were happy to receive work. “I love telling an artist that they got a job,” she says. “I say, ‘Am I catching you at a bad time?’ and they say, ‘Not for you, Lori!”

Her clients are mostly Fortune 500 executives and university administrators—those who either can afford the cost (ranging from $18,000 to $60,000 and up) or need a portrait to commemorate history, or both.

Portraits are often done of politicians and military generals, and until recently, American taxpayers footed the bill. Public backlash against Donald Rumsfeld’s $50,000 portrait brought this spending to light, and the Obamas raised private funds for their portraits. Donald Trump made this practice law in 2018, by signing the Eliminating Government-funded Oil-painting Act (the EGO Act).

The hardest part of Polson’s job is finding new clients, but selecting an artist and managing the process is also complex. She’s involved from start to finish. With new clients, she asks questions to narrow down the 40-plus artists she represents to 10 or fewer: Traditional or contemporary style? Include their spouse in the picture? How do they want to be remembered? Some institutions prefer an established artist whose work will increase in value. She has the client choose from a lineup of portraits by her selected artists, and then arranges a conference call with the artist and sitter. She advises the client on what to wear and on appropriate backgrounds or objects to include, and warns against a haircut the day before, because the hair won’t lie naturally. Some artists photograph their subjects; others paint from life. Either way, Polson is there but doesn’t interfere, except to fix a wrinkled shirt or crooked collar. After that, she acts as go-between, eliciting feedback from the sitter, who might want to look thinner or more attractive but doesn’t feel comfortable telling the artist; sometimes she passes along a request from the artist about what to wear. When the portrait is finished, she helps choose a frame and then attends the unveiling, celebrating this months-long process.

“Often, my clients don’t even want a portrait of themselves,” she says. (Often, an institution will request portraits of its leaders.) “Through the process we become friends, and by the end, they love their portraits.”