THE SEARS CATALOG

A MASTER CLASS IN MERCHANDISING

by Daniel Levinson Wilk, professor of American History · June 6, 2022

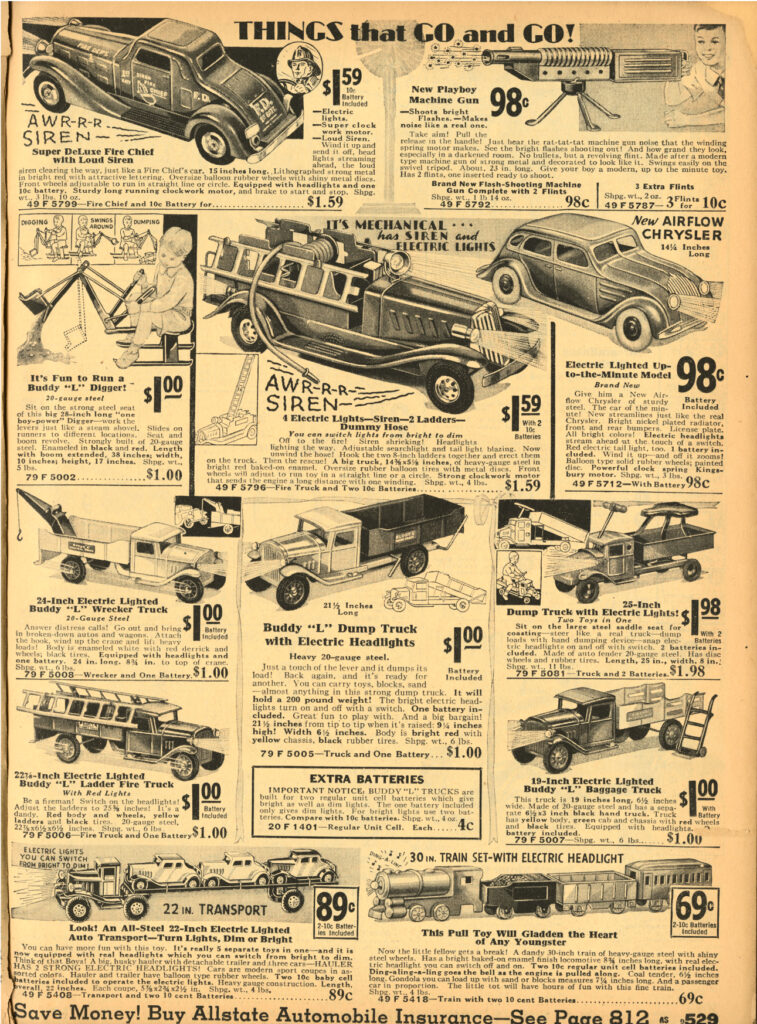

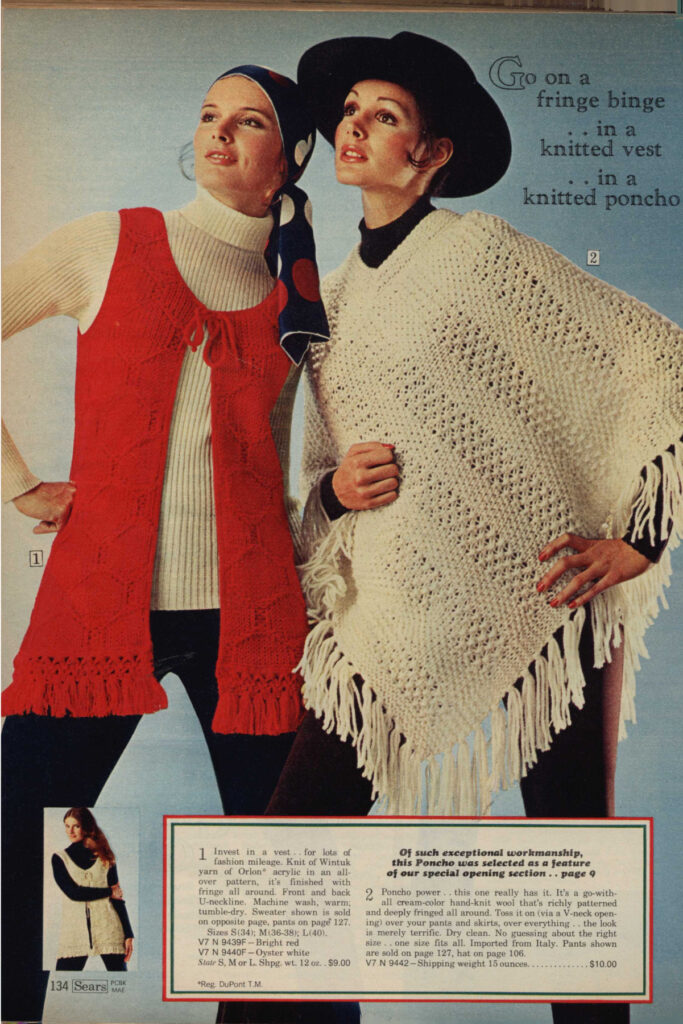

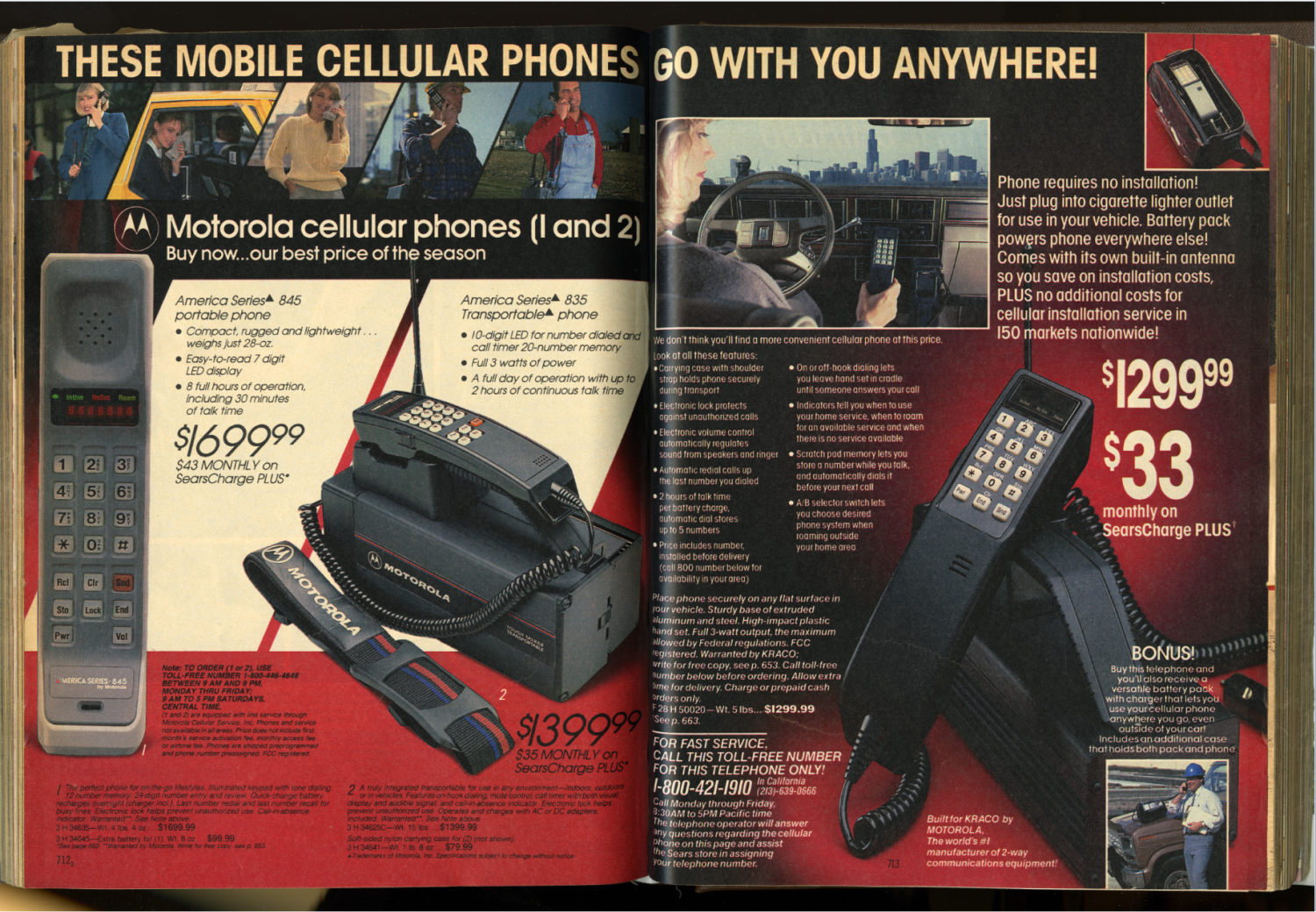

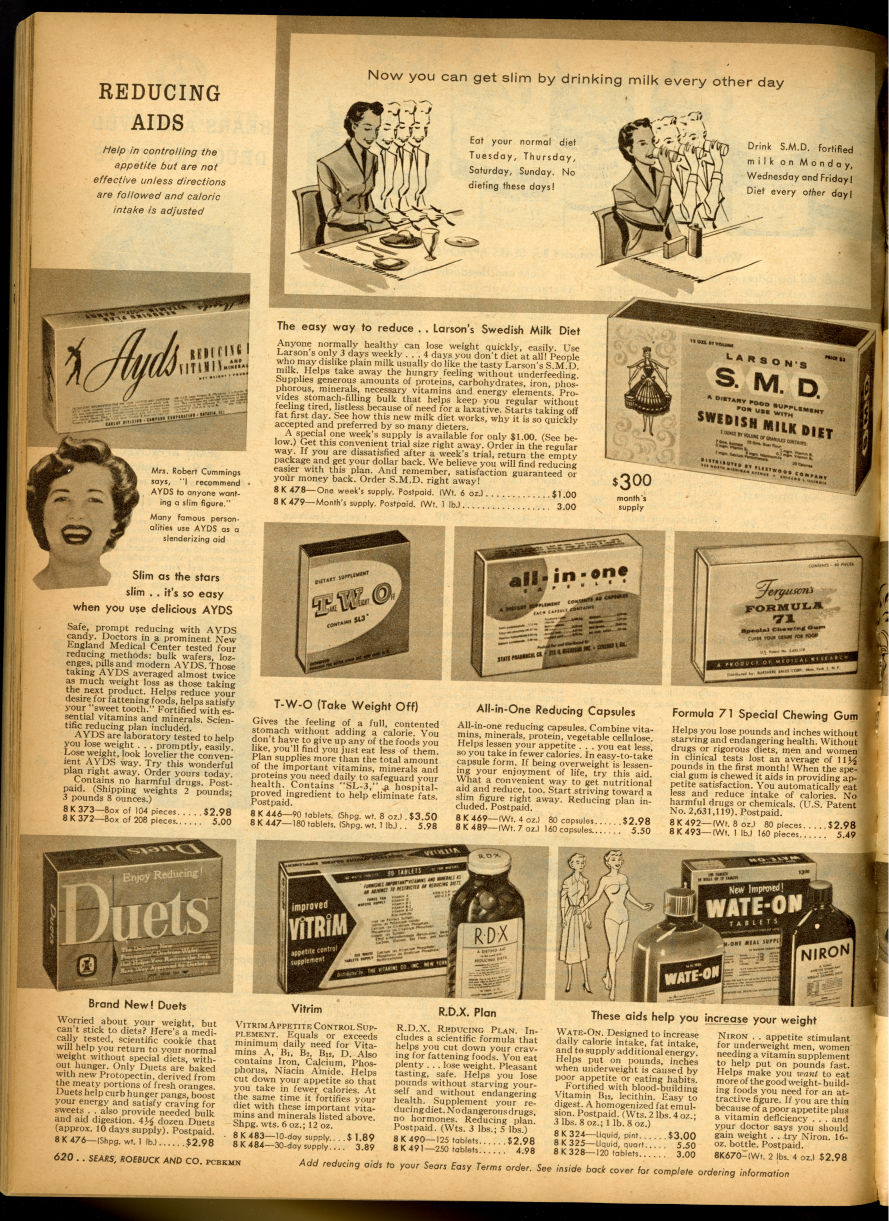

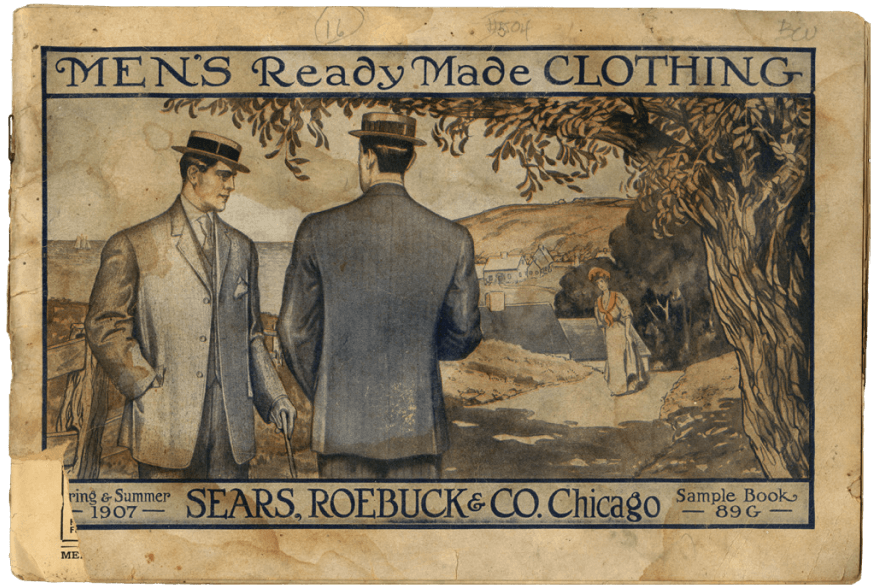

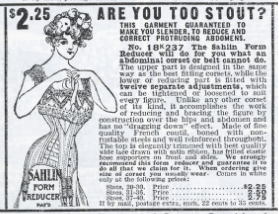

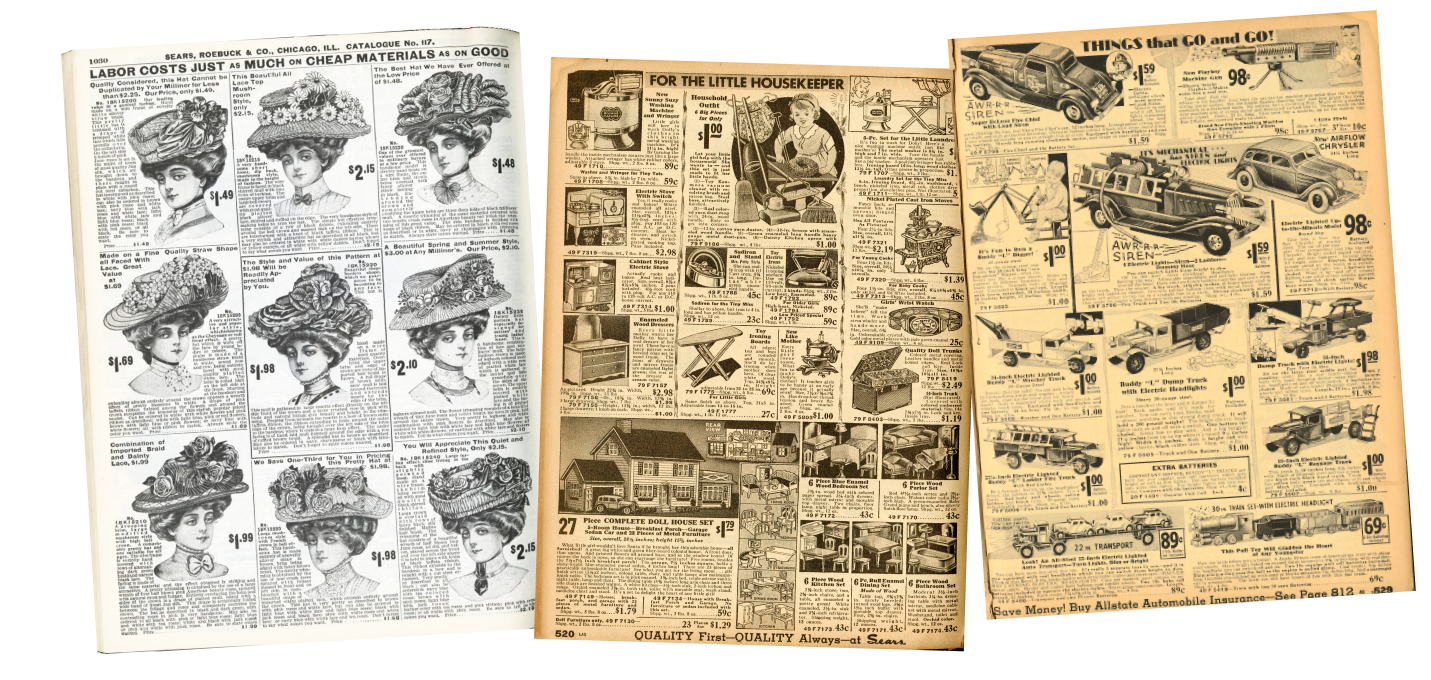

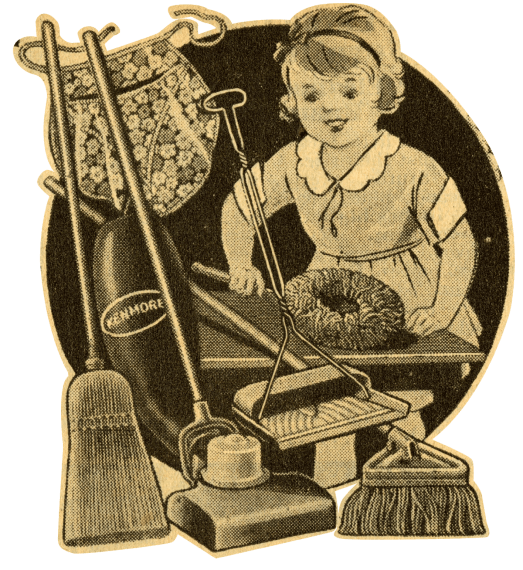

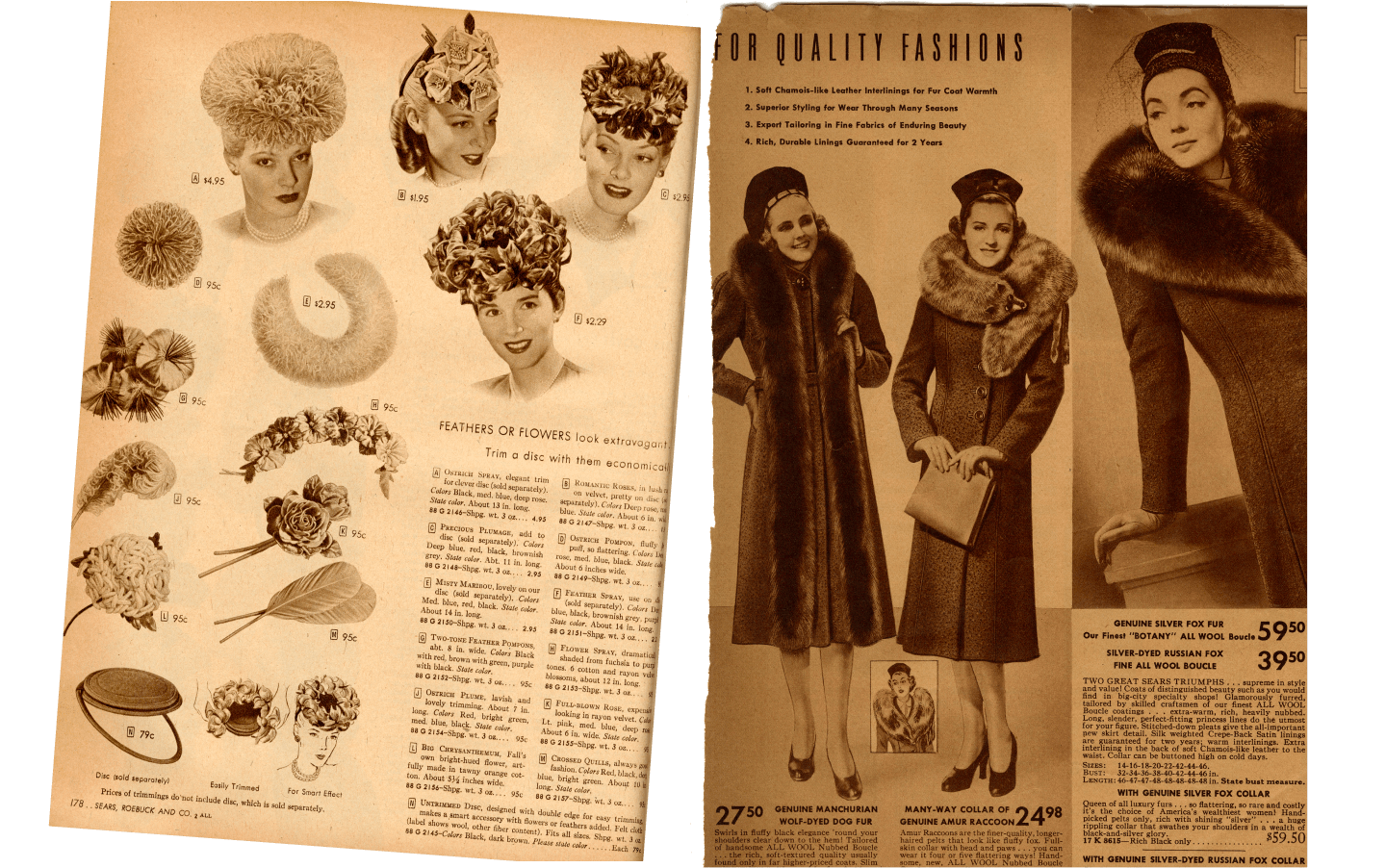

America is the land of consumer seduction, and for most of the 20th century, the Sears catalog was its capital. It was a 1,000-page cornucopia of lively artwork and enticing copy, an astonishing array of products, everything new and seemingly essential.

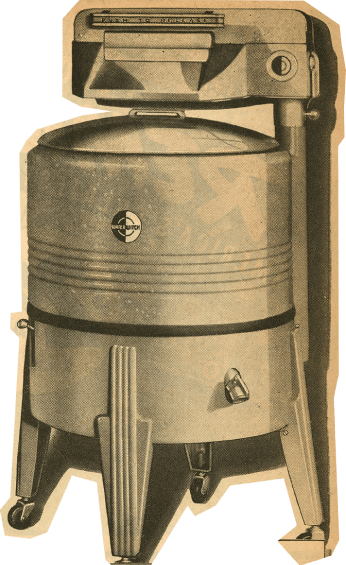

“It was the American dream in this one book,” Instructional Services Librarian Maria Rothenberg says. You could buy clothes—or a sewing machine to make them yourself. You could buy dishes—and a dishwasher to clean them. You could even buy a house, though it came in modules that you or a builder would assemble.

The Sears catalog was “the first Amazon,” as Rothenberg teaches in a course about American products back to 1900. Shawn Grain Carter, associate professor of Fashion Business Management, tells students that the Sears catalog and its rivals were the origin of every direct marketing technique used today. Indeed, the catalog figures prominently in a number of FIT courses. And the Gladys Marcus Library has nearly every issue, mostly in Special Collections.

Leslie Blum, retired assistant professor of Communication Design, says Sears was a champion of cutting-edge industrial design. For example, Raymond Loewy redesigned the Coldspot refrigerator for Sears in 1935, with clean lines and simple controls. It created a new aesthetic for home appliances, tripling the company’s refrigerator sales and boosting the profile of industrial designers everywhere.

And those Sears house kits were a major innovation. The Arts and Crafts–style homes featured in the catalog were simple, sturdy, and more affordable than similar homes in Britain, Blum says. Their floor plans reveal a lot about American habits in past decades, Rothenberg says. “In the earlier homes, there’ll be no closets, because people didn’t have a lot of things. There’ll be no bathroom. People bought their refrigerator before they did their bathroom.” Eventually, the era of outhouses and chamber pots ended, and the house kits started including a room with a toilet.

There were earlier experiments in mail-order catalogs—Ben Franklin circulated one that sold books, and seed catalogs for farmers were popular in the early 1800s—but historians generally date the modern industry to a single page Aaron Montgomery Ward mailed out in 1872, listing 163 items for sale. A quarter century later, the Montgomery Ward catalog neared a thousand pages and sold $7 million of goods each year.

Richard Warren Sears and Alvah Curtis Roebuck followed in 1888, with a catalog that offered watches and jewelry. They diversified their goods in the early 1890s and became Ward’s main competitor, eventually beating him in sales.

Sears always tried to keep its catalog a little thinner than Ward’s. “Mr. Sears knew,” Rothenberg says, “that when housewives straightened up, they put their Montgomery Ward catalog under the Sears catalog, so the Sears catalog would always sit on top. Pretty smart, right?”

Sears borrowed department store innovations: sell a wide assortment of products, standardize prices and ban haggling, offer satisfaction guarantees. But catalogs added important new advantages. By using the federal postal service—a vast, government-subsidized system of transport and communication—they could serve rural areas and enable farm families to access the bounty of mass market capitalism. It was a long buggy ride to Chicago to browse fashionable shops, so rural customers stayed home and browsed through the catalog instead.

And anyone could dream over its pages. Novelist Harry Crews, who grew up dirt-poor in Bacon County, Georgia, wrote, “The federal government ought to strike a medal for Sears, Roebuck Company for sending all those catalogs to farming families, for bringing all that color and all that mystery and all that beauty into the lives of country people.”

Like e-commerce today, catalogs reduced the contact between workers and customers. You had to share your name, address, and purchasing choices with some strangers in Chicago, but you didn’t have to see anyone face-to-face, not even your mail carrier if you timed it right. This appealed to poorer and less literate shoppers, whom clerks sometimes treated with “supercilious haughtiness,” as department-store historian Susan Porter Benson noted. Sears home office employees would do their best to interpret your order form, and if they got it wrong, you could send the item back. If you wrote in another language, Sears had employees who could translate.

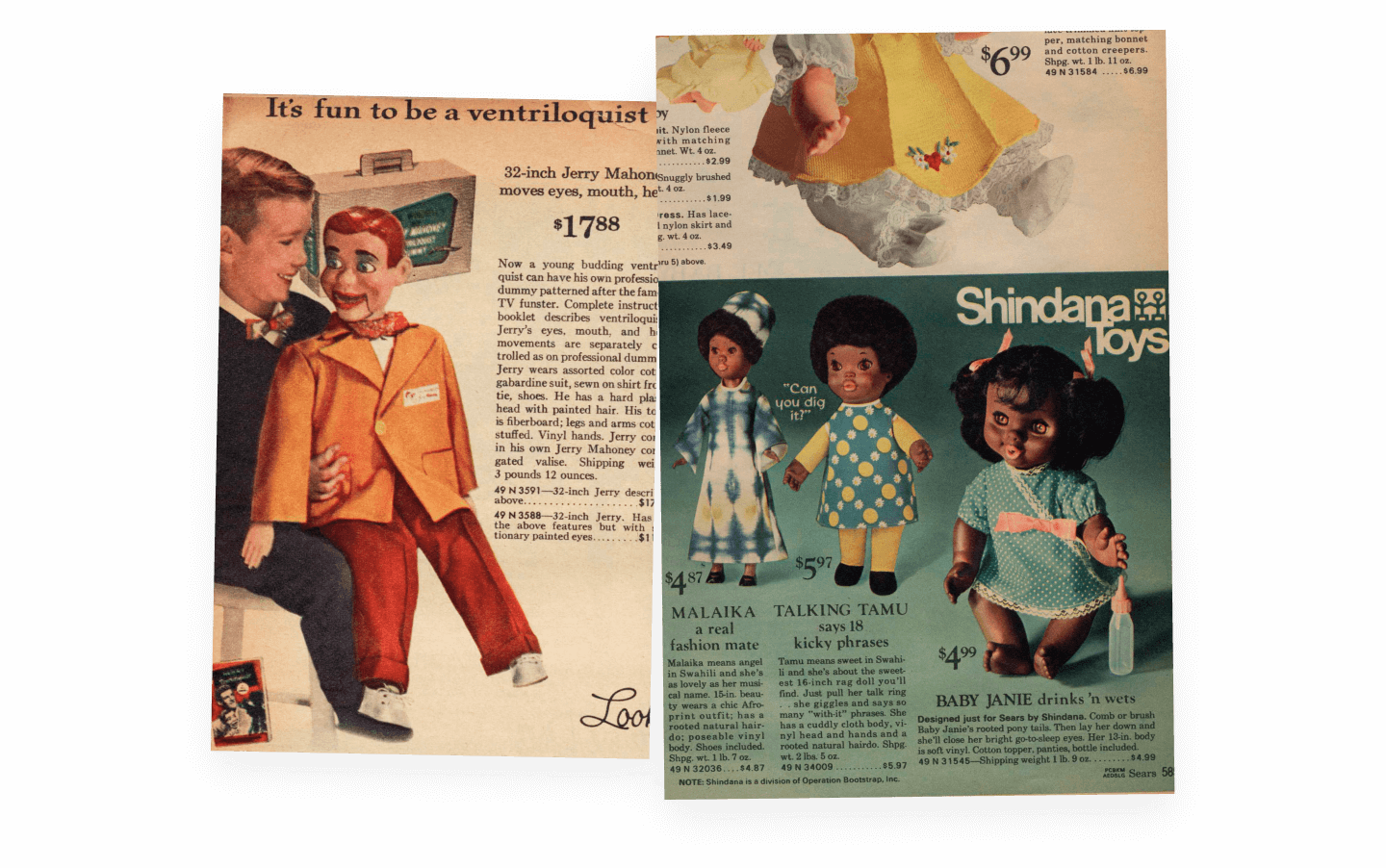

Less contact was especially appealing to Black customers, Carter explains. “[They] evaded Jim Crow discrimination by shopping the catalog. Some still own their Sears catalog homes.” Catalogs allowed Black customers to avoid indignities imposed by racist store clerks—price gouging, humiliating treatment, refusal to sell products deemed too fancy for them, credit restrictions. White supremacists saw Sears Roebuck as a threat, accusing the founders of being Black men and holding Saturday night bonfires to burn the catalogs.

Julius Rosenwald, Sears’s second CEO, did even more for the Black community after being introduced to legendary educator Booker T. Washington. Rosenwald donated matching funds to build more than 5,000 schools for impoverished children across the South, educating the likes of Maya Angelou and civil rights leader and politician John Lewis. There were limits to the company’s commitment to social justice, though. Sears stores in the South followed Jim Crow laws, limiting African Americans to employment as janitors, cooks, servers, or other behind-the-scenes roles.

Starting in the 1920s and accelerating after World War II, Sears opened more stores because Americans were buying cars, moving to cities, and venturing into suburbs, making the nation less rural, less isolated, and less reliant on mail order. Department store sales grew over the decades, and the traditional Sears catalog was finally discontinued in 1993, one year before Jeff Bezos founded Amazon. With the rise of online shopping and changes in consumer habits, Sears stores are disappearing.

Vincent Quan, associate professor of Fashion Business Management, attributes Sears’ problems to its “inability to pivot effectively to e-commerce. In addition to the assault from e-commerce and Amazon, competition from Walmart and other big-box retailers resulted in an organization unable to compete.”

Today, with only 23 Sears stores reportedly left in the U.S., the catalog remains an icon, a reflection of mass material culture and consumption over a century. It is a talisman of the American heartland that we mythologize as the moral center of our national experiment.

And it lives on in our collective memory. Matthew Petrunia, associate professor of English and Communication Studies, was fond of the Sears Christmas Book. “I remember feeling jealous of the kids pictured in the catalog with their cool roller skates, guitars, wooden chess sets, and especially the ones lucky enough to have themed NFL bedrooms—everything from the bed sheets to trash cans plastered with your team’s colors and logos.”

The catalog is indispensable for designers looking to evoke the past. “It’s crucial for unlocking accurate period details,” says costume designer Jeriana San Juan, Fashion Design ’04, who recreated looks for Netflix’s series Halston. Otherwise, it lurks in attics and archives, a nostalgia trip. April Calahan, MA ’09, Special Collections associate and curator of Manuscript Collections, says, “Growing up in the late ’70s, I remember flipping through the pages. I don’t think there’s any substitute for that.”

Daniel Levinson Wilk, professor of American History, is on the board of directors of the Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition and writes about waiters, elevators, and the history of the modern service sector.