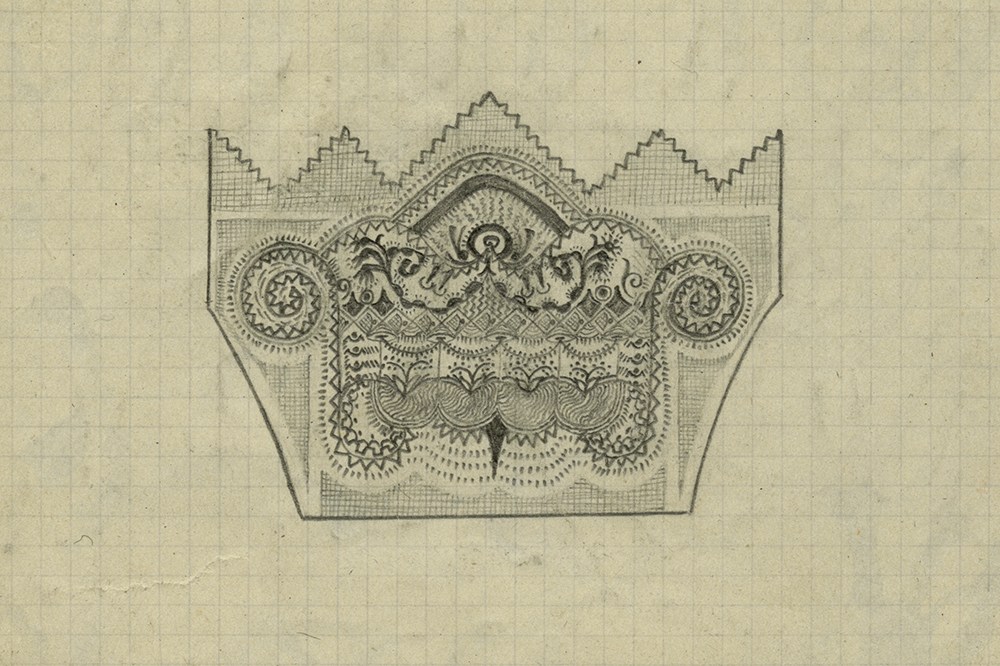

Sometimes the habits we develop to distract ourselves are more important than we realize. Valerie Fuchs’ small, intricate pencil sketches are a perfect example. Her son Thomas Fuchs recently donated her meticulous drawings, along with other artifacts related to her career, to FIT’s Special Collections. Only they weren’t created under ordinary circumstances. She drew them while hiding from the Nazis during World War II.

Valerie was born in 1916 in what is now Martin, Slovakia. She grew up attending fashion shows with her father, a department store owner. “He had the eye,” Thomas said. “My mother inherited a lot of his talent.” She married Ladislav, a dentist, in the late ’30s, but restrictions on Jews were already beginning.

Eventually, a local politician gave Ladislav a basket of apples concealing a gun and urged him to go into hiding. The Fuchses first found refuge in a basement, and then a Christian family hid them in their attic. They waited there for a year—and Valerie sketched.

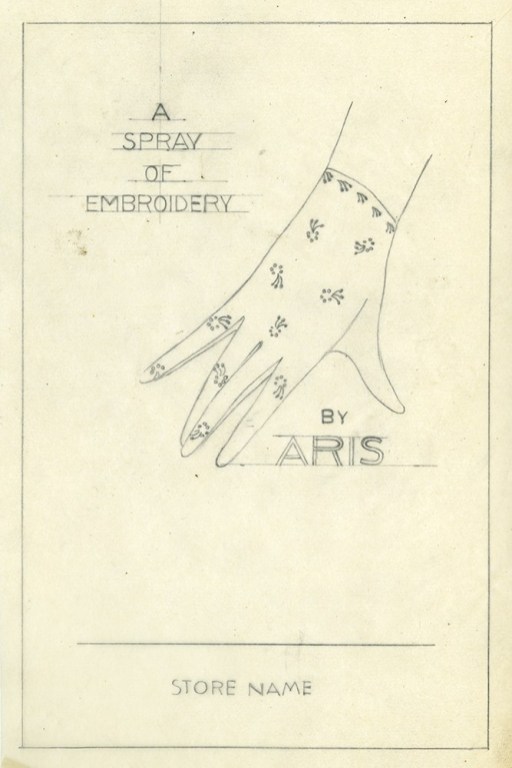

A few years after the war ended, the Fuchses, along with one-year-old Thomas, moved to New York City. Unable to be a dentist in the U.S., Ladislav worked in a thermometer factory, while Valerie took in freelance textile design work. In the early ’60s, she got a job at Aris Glove Company as its exclusive designer and helped push several innovations forward. These included an early version of a shaping bodysuit and a special, stretchy stitch. “She was doing isometric exercises and martial arts,” Thomas recalled. “Isometrics is like resistance training, and the stitch had resistance. So she said, ‘Why don’t we call this Isotoner?’” Eventually, Aris was renamed Isotoner.

Valerie worked at the company for 16 years before joining her family’s business—Allied Brass, a bathroom fixture company. And she extended her skills to designing the products with Thomas. He sold Allied Brass in 2005 and Valerie died in 2013 at 97 years old, but she made a clear impact while with the company. “My mother and I cultivated a culture of innovation,” Thomas said. “She was a real Renaissance woman.”