Bauhaus artist Anni Albers (wife of Josef) and Sheila Hicks (once Albers’ student and now a textile icon) paving the way. The practice has historically struggled to get the same level of recognition as painting and photography because it’s “traditionally been relegated to women’s work and the fringe,” Jeyaveeran says.

She acknowledges, however, that things are changing. “In the last 10 years or so, traditional craft mediums like fiber art have started to become recognized by the art world,” she says. Recent exhibitions in New York featured the work of textile artist Diedrick Brackens, at the New Museum, and the late sculptor Mrinalini Mukherjee (who often used dyed and woven hemp rope), at the Met Breuer.

Meltzer attributes this resurgence of interest to “a desire to get back to something tactile” in an increasingly digital world. People are recognizing the importance of the very human, multisensory experience that has long attracted artists to fiber art. But this can lead to a problem in museums and galleries, Kleinman says: “People try to touch the art.”

Hallie Meltzer

A seated figure covered with skin made of swatches. Crocheted raffia pieces. A mixed-media American flag. All of these are part of the portfolio of Hallie Meltzer ’08. “I’ve never been married to one specific technique,” she says. “I want to see how many different things I can do.”

Coming from a family of knitters and makers, “textiles had been with me my whole life,” she says. She started her career working as a costume designer but created fiber art on the side. She quickly realized the profession’s erratic work schedule, low pay, and high burnout rate were not for her—so she switched her focus and went to FIT to study textile design. “I love the tactility of it,” she says. “I love feeling with my eyes.”

She’s also a senior designer for Richloom’s Platinum Division, which makes fabrics for the home. Her more recent pieces have been inspired by a major aspect of her job: designing with a computer. “I’m trying to bridge the digital and the tactile,” she says.

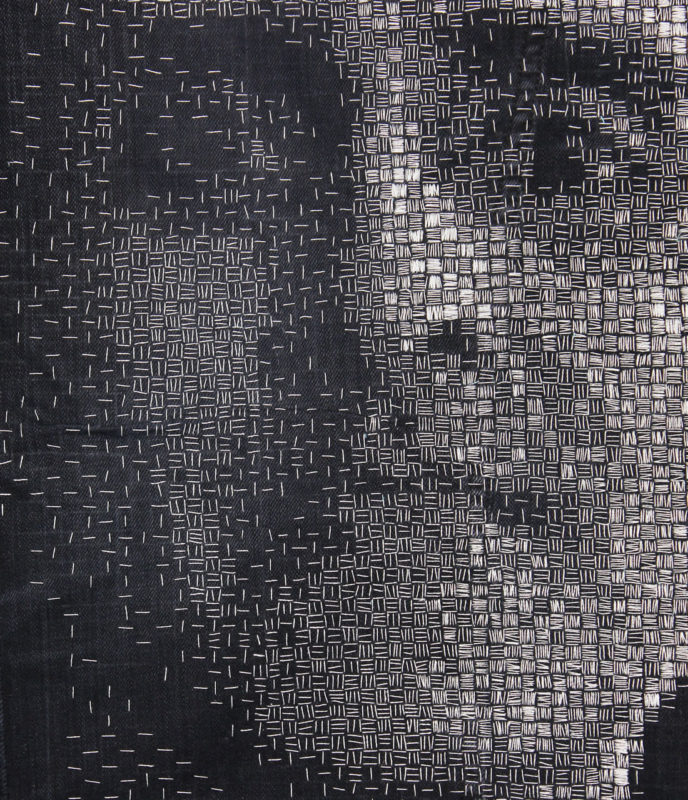

For the work featured here, which has been shown at Gallery FIT and the Brooklyn Waterfront Artists Coalition, she took a black-and-white image of her husband and embroidered it on denim.

“I used binary code for stitching each shade of gray,” she says, referencing the computer code that transmits data via a system of ones and zeros. A stitch represents a one and a space represents a zero, so she created gradation by reducing the number of stitches.

Though recent works like this have been figural, she’s ready to explore something different. “I’ve been trying to get myself to abstract more,” she says.

Ruth Jeyaveeran

Say “felt” to Ruth Jeyaveeran, assistant professor of Textile/Surface Design, and she’ll talk about microscopes and Mongolia. Materials like felt are part of everyday life, she says, but people don’t usually understand where they come from.

Felt is perhaps the most ancient of textiles. Mongolians have used it to make yurts for thousands of years. Felt is made by compressing fibers and exposing them to heat, friction, and moisture. If you magnify wool fibers, Jeyaveeran explains, they look scaly. When you add hot water and agitate the fibers, the scales open up and bond naturally. Jeyaveeran makes the felt she uses in her own work, enjoying the contrast between the “cool, low-tech” material and the advanced technology she often employs.

She worked as a book illustrator (and wrote a few books herself). “I ended up using a lot of textiles as illustrations,” she says. A textile designer saw her work and suggested she go back to school and focus on the practice. After graduating from FIT, she designed home fabrics, apparel, and accessories for companies like Kate Spade and West Elm.

Recently, she’s been experimenting with laser cutting and digital embroidery on felt in her series of art pieces “After the Flood,” which highlights the consequences of climate change. It’s been included in exhibitions at Gallery MC, Site: Brooklyn, and more. The Seven Seas (above) depicts the formula for carbonic acid, which is formed when carbon dioxide dissolves in the ocean, and can harm marine life. “I like the contrast between the rigid formula and the fluid, felted piece.” This tension between science and nature, tradition and modernity, Jeyaveeran says, is “the whole crux of textiles.”

Jessica Vitucci

Jessica Vitucci ’16 has loved making portraits since high school, but when a teacher gave her a frame loom, she departed from the traditional route of painting or drawing. Making textiles “felt less limited,” she says. “It could be fashion. It could be for the home, it could be fiber art.”

After FIT, she landed her dream job as a rug designer at ABC Carpet & Home. But, as with most design gigs, the work was based on trend research, not personal inspiration. “When I came home, I didn’t want to put things on repeat anymore,” she says.

She returned to portraiture, using textiles as a medium. For works like Michelette, shown above, she takes a photo of the subject, makes a drawing, traces the drawing onto fabric, and then embroiders it with yarn. Sometimes she prefers to highlight the process itself, showing the backs of her pieces. “I think they come out just as beautiful, if not more, than the front,” she says. “The order in which the thread goes is really special.”

Last year, she temporarily relocated to Rhode Island. “I was able to put more time toward my process and get out of the rush of New York,” she says. While there, she worked with fiber artist Anastasia Azure and showed in the juried exhibition Twisting Fibers: An Art for All Reasons. Now back in New York, she’s designing for the rug company Well Woven and pushing her portraiture forward even more. “I’m still in the early stages of exploring it,” she says.

Cynthia Alberto

When Cynthia Alberto ’02 was younger, her family would go home to the Philippines and bring back textiles. “I never really paid attention,” she laughs. Years later, however, weaving textiles became pivotal in her life. “It healed me,” says Alberto, who took solace in the craft after going through a divorce. “The repetitive motion … quieted my mind.”

With a degree in computer science, Alberto worked on Wall Street in computer programming and in sales at The Village Voice, while making art in her free time. She often incorporated sewing into her pieces and wanted to transform her paintings into textiles. With this in mind, she went back to school at FIT, then worked with Tibetan rug evangelist Stephanie Odegard.

In 2007, she opened her Brooklyn studio, The Weaving Hand (which also sells weaving supplies). It teaches traditional and modern techniques and sustainable practices through in-house classes for all ages, public events at spaces like Pioneer Works and Ace Hotel, and outreach programs for the underserved.

The studio aims to instill a sense of well-being and community in its students. Weaving can strengthen motor skills and concentration, while building self-esteem. “It’s personal expression, and you get the satisfaction of completing a project,” Alberto says. “Plus, these groups are talking with each other, interacting. … It’s social healing.”

Alberto, who was one of the first-ever artists in residence at the Museum of Arts and Design, integrates the idea of community in her own work. The series Techno Love (pictured here), made up of 30 woven cocoons, was inspired by the feeling of connecting with a community through music.

And she still thinks about the textiles she ignored in her youth. Though she has collaborated (both independently and through her studio) with noted fashion brands like Proenza Schouler, EDUN, and Turnbull & Asser, she also works with an international community of weavers to preserve ancient traditions. Sometimes this commitment drives Alberto to rifle through her family’s closets. “Now I ask them, ‘Where are [those textiles]? Do you still have them?’”

Ruben Marroquin

For Ruben Marroquin ’19, his rocking chair is not just a source of inspiration—he wants to put it in a piece. Marroquin wraps everyday objects in yarn, and nothing’s off-limits. “I had a Buddha statue in my room once,” he says. “I wrapped it.” Marroquin originally focused on fine art and painting, but the three dimensional aspect of textiles attracted him to fiber art. “I increasingly started searching for volume, a sculptural aspect,” he says.

Growing up in Venezuela and traveling around Latin America also played a part. “I was drawn to traditional Venezuelan techniques, like basket weaving and huts built with palm leaves,” he says. He moved to New York in 2004 and received an AAS in Textile/Surface Design from FIT in 2009. After a break, he finished his BFA in 2019.

While at FIT, he developed his sculptural wrapping technique. He was working with bamboo to make Japanese kites for a portfolio review, and then started incorporating the material into more personal pieces. He would make armatures out of bamboo and cover them with yarn. To create even more volume, he used the yarn to wrap found objects into the pieces.

He employed a similar technique, using aluminum frames, to create the art featured here, which was commissioned by noted Los Angeles–based interior designer Kelly Wearstler. When she saw Marroquin’s work on Tumblr, she requested pieces in muted tones, which now reside in the home of comedian Sebastian Maniscalco.

Marroquin continues to create personal work and collaborate with Wearstler, but “one of my big passions is teaching,” he says. He’s held weaving workshops at nearly two dozen schools in Connecticut, at senior centers, and at FIT as an artist in residence in spring 2019. “It’s rewarding to see how much people enjoy it,” he says.