MARKETING IS AN ANCIENT PRACTICE.

As early as 2500 BCE, Mesopotamian bakers stamped bread with logos to identify the maker and assert quality. In Pompeii, mosaic advertisements for a certain manufacturer’s fish sauce date from the first century BCE. Over millennia, the field has transformed immeasurably, producing thousands of groundbreaking moments. Neil Brownlee, a 40-year veteran of the advertising industry who has created campaigns for ESPN, MTV, and Reebok, discussed six of his favorites.

Brownlee, who teaches advertising and direct marketing, says it’s all about enhancing the relationship between the customer and the promoted item. “Don’t make a promise with your marketing message that your product can’t live up to,” he says. “It’s a relationship built on trust.” Sometimes honoring that trust requires an adjustment in tactics—or the choice to scrap a new product altogether. Once, for example, Brownlee was working with a major soft drink company that planned to introduce flavored root beer. “We did focus groups all over the country. An older guy in one group asked, ‘Why are you messing with root beer? It’s perfectly good.’” The criticism resonated with others, and the new sodas never materialized.

Today’s marketer faces formidable challenges. Ancient bread bakers never had to contend with callouts on social media if a loaf was soggy. Netflix and other streaming services offer commercial-free upgrades, while digital platforms like Facebook allow users to block ads they dislike. Audiences are atomized and attention spans are shrinking. “We’re dealing with a cluttered world,” Brownlee acknowledges, yet he says certain fundamentals still apply. “To succeed in marketing, you have to understand two things: One, the product itself. What does it do? Where and how was it made? And two, the consumer. Who are they? We are trying to motivate consumer behavior, so what problem are they trying to solve?”

That’s not to say that good marketing necessarily targets logic. Coca-Cola, for example, attained legendary status in the ad world with its 1993 campaign featuring cuddly polar bears. “Pepsi is about the individual experience—‘Be cool’—but Coke’s premise has always been about sharing,” Brownlee says. The bears were inducted into the Madison Avenue Advertising Walk of Fame in 2011. Then there’s “Make America Great Again,” a slogan that helped catapult an unlikely candidate into the White House. “That line was stolen from Ronald Reagan,” Brownlee says, “but it spoke a language Trump’s audience could understand.’”

Encompassing moments large and small, curious and quixotic, here is Brownlee’s personal list of marketing highlights. Click on the bubbles to read more.

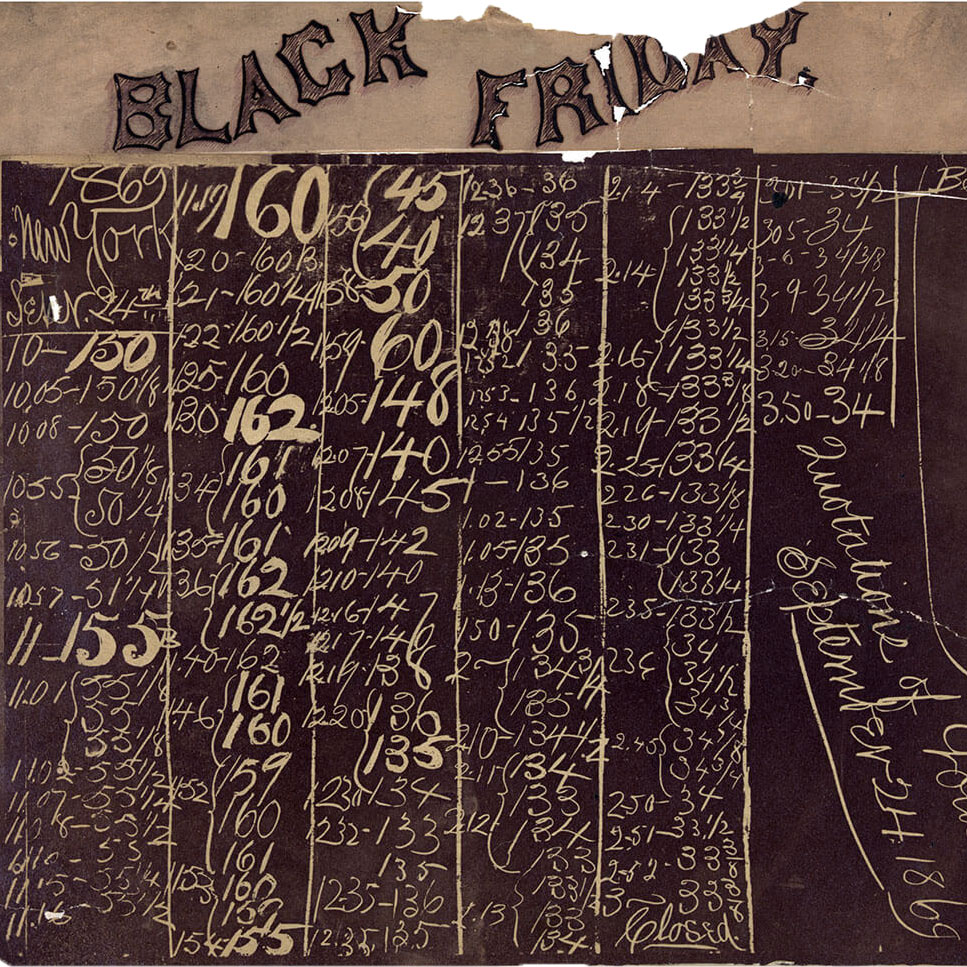

In American history, the term “Black Friday” originally referred to the panic of 1869, in which the stock market crashed and ruined many investors.

The phrase’s association with shopping evolved over time. Until 1939, Thanksgiving was celebrated the last Thursday of November, but that year it fell on the last day of the month. President Franklin Roosevelt, hoping to jump-start an economic recovery to end the Great Depression (and placate retailers who wanted a longer holiday shopping season), issued a Presidential Proclamation moving Thanksgiving to the second-to-last Thursday. Congress ratified the change in 1941. In the 1960s, Brownlee says, the Philadelphia Inquirer began referring to the day after Thanksgiving as Black Friday because that’s when stores would get “in the black,” i.e., turn a profit, by advertising huge sales that bargain hunters couldn’t resist.

Some sources, however, claim the term was negative, invented by Philly police overwhelmed by a wild influx of shoppers. Many retailers didn’t want to be associated with black because, Brownlee says, “it sounded like mourning or something depressing.” Either way, by 2005, Black Friday was officially the biggest shopping day of the year, accompanied by now-legendary scenes of frenzied hordes grabbing merch. “People died, got trampled by mobs, trying to get a deal,” Brownlee says. (Since then, the rise of online shopping has led to fewer crowds.) In the 21st century, the phenomenon became global, with New Zealand, the Netherlands, and Saudi Arabia, among other countries, implementing their own versions.

The black board in the New York Gold Room for Sept. 24, 1869, shows the collapse of the price of gold. Photo: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

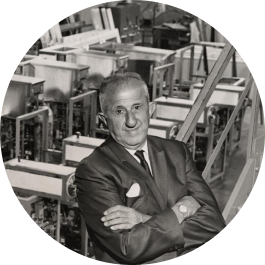

Tom Carvel, founder of his namesake soft ice cream franchise (as of 2018, there were 371 franchises worldwide), pioneered a DIY marketing approach starting in the 1950s.

Dissatisfied with existing Carvel radio spots, he wrote and performed his own in his distinctive gravelly voice. When he began appearing in TV ads for the company in 1971, audiences were startled, Brownlee says. “He was not a beauty by any stretch of the imagination. Most ads at that time featured women in glamorous gowns,” or blandly handsome TV actors. “Tom came off as an average guy,” and his down-home, honest approach was appealing. Customers ate it up, along with Carvel’s Fudgie the Whale and Cookie Puss cakes. With Tom on camera, the company saved money on talent, but the real benefit came from his plainspoken authenticity and implied accountability. “It was influential,” Brownlee says. “Over time, owners of companies would take the microphone as a way of saying, ‘If something goes wrong with the product, you know who to blame.’”

Imitators followed: Dave Thomas of Wendy’s, Orville Redenbacher of popcorn fame, and Frank Perdue, touting his “tender chicken.” Of the latter, as Brownlee tells it, “Frank asked the marketers, ‘Why me? I’m bald and I have a high voice.’ ‘Because you look like a chicken, Frank.’” Tom Carvel made the spots through the 1980s; he sold the company in 1989 and died a year later.

Tom Carvel image: Pat Carroll/NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images; Cookie Puss image courtesy of Carvel

Today, when the 24-hour news cycle seems to have accelerated to 24 milliseconds, it’s easy to forget that weekly magazines once broke news.

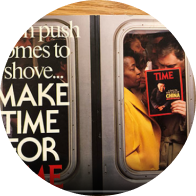

Brownlee helped create the 1992 campaign “Make Time for TIME.” “Time magazine was our account,” he says. “USA Today was adopting new technologies. They had stories from all over the world beamed in via satellite and printed around the country with full-color photos. We wanted the audience to see the newsstand appearance of Time as something special.” The multichannel campaign (print, radio, TV) placed special emphasis on TV ads, which aired Saturday and Sunday to promote the Monday arrival of Time.

It was the early days of the internet, and the new technology was essential in making the spots, which prominently featured the magazine’s cover. “We put a lot of pressure on the editors,” Brownlee says, “because they tended to delay decisions about the cover to the last minute, and we needed them early to make the ads.” Covers were emailed to Brownlee’s team late Thursday so the ads could be finished over the weekend. Like the famous “Perception vs. Reality” campaign for Rolling Stone, the Time campaign communicated to advertisers that its audience was on the cutting edge of a new, speed-addicted world.

Brownlee helped stage this image, which ran in print publications. “The fellow reading the magazine was the agency account exec for Time. The African American woman was the agency receptionist. The ad shows busy commuters who, in spite of their hectic schedule, made time for Time because they didn’t want to miss out on the latest news.”

“When I teach my Direct Marketing class, I tell my students to watch half an hour of QVC,” Brownlee says. “Many of them will say, ‘I don’t have a TV.’

“‘You can watch it online,’ I say. They come back fascinated.” Growing to reach 350 million households in seven countries since its 1986 launch, “the 24-hour, live department store,” as Brownlee calls it, might look like a series of bland infomercials to the uninitiated, but to a marketer, the home shopping channel represents real opportunity. Fashion, technology, tools, jewelry, back-to-school offers: Endless categories of merchandise are hawked, with experienced, telegenic salespeople beamed directly into consumers’ homes. Viewers feel personally connected with their favorite hosts and company reps (and thus their products), and are excited to talk to them on air. Among other pluses, it allows the consumer to avoid actual, poorly organized department stores, with the added bait of a quicksilver return process.

“Not only is it convenient, it’s hassle free. That’s great marketing,” Brownlee says. QVC does take part of the profits, he notes, “but QVC is more than just a way to sell something; it’s an investment. Your products get exposure, and you also have a new crop of customers that you can add to your database. Everything now is data, data, data.”

QVC host Lisa Robertson and Dennis Basso, Fashion Buying and Merchandising ’73, at a Super Saturday benefit in 2007. Basso sells affordable fashion and home decor through QVC. Photo: Matthew Peyton/Getty Images

“The first time I heard of Amazon was back in the ’90s,” Brownlee says. “I knew this fellow in Brooklyn who said, ‘You should go to Amazon and get books for one-tenth of the price.’”

The retailer that needs no introduction showed marketing genius from the get-go, he says. In the beginning, “Jeff Bezos chose to sell textbooks because he could get them for pennies on the dollar.” Often heavy, expensive to store, and prone to becoming outdated, textbooks were a liability for publishers, but Bezos saw an opportunity to reach his target market. “Who buys textbooks? Smart people! And who has the most influence in the world? Smart people! That’s what marketing is all about,” Brownlee says. He has his students scrutinize TV ads during specific programs for clues about whom the marketers are trying to reach. Bezos had in mind the same audience as the classic news programs Meet the Press and Face the Nation. “Because of their intellectual status, viewers of those shows were the people who make decisions: Washington lobbyists, congresspeople, industrial leaders. Opinion makers—the influencers of the ’90s.”

Word of mouth helped publicize Amazon at first, but Brownlee says Bezos was also an early adopter of computer algorithms that recommended items based on users’ buying and browsing history. The site also made use of direct marketing through targeted emails that alerted shoppers to sales in their favorite merchandise categories. Today, of course, Amazon isn’t just for smart people; it’s for everyone—and that was always the intention, Brownlee says. “Bezos didn’t call it Amazon as a reference to Greek mythology; he was referring to the river that spans a continent and has a seemingly infinite number of tributaries.”

Jeff Bezos’s office in 1997, as shown in a 60 Minutes interview.

Boxes image: Shutterstock

TV advertisers tend to jam as much information as they can into 30-second spots, often to unintentionally humorous or, worse, bewildering effect.

On YouTube, marketers have as long as they want (the maximum upload is 12 hours, according to the site), assuming they can keep the viewer’s interest, but there’s another factor working in their favor on the popular video streaming site. Marketing, Brownlee explains, falls into two categories: outbound, in which advertisers send messages to the consumer; and inbound, in which the consumer seeks out the brand—and that’s where YouTube comes in. “It’s the ultimate place for how-to: how to put siding on a house, sew a blouse, or bake a cake,” he says. Top YouTube advertisers for 2021–22 included Hulu and Expedia, which makes sense, Brownlee says. “People go to YouTube searching for new shows to watch, and Hulu is there; or they want to find out about what’s going on in Mexico,” they click on a video guide to Mexico City (made by Expedia, with conveniently embedded links to the travel site) and wind up booking a trip. Anyone can have a YouTube channel (uploads are free), and apparently anyone can create addictive content. “It’s the perfect place to tell your story—and your product’s story.”

Audiences come for simple information or entertainment, but wind up sucked into the feed of related videos. YouTube’s algorithm fuels obsessive attention, and the more attention your video gets, the higher your content gets ranked on the list of related videos. The site’s best channels are cannily curated and designed to whittle away randos and attract the marketer’s ideal niche. “A YouTube channel should be designed for a specific market segment,” Brownlee says. “When I ask students who their market is for any given product, they’ll always say, ‘Everyone.’ And I say, ‘You don’t have enough budget for that.’”