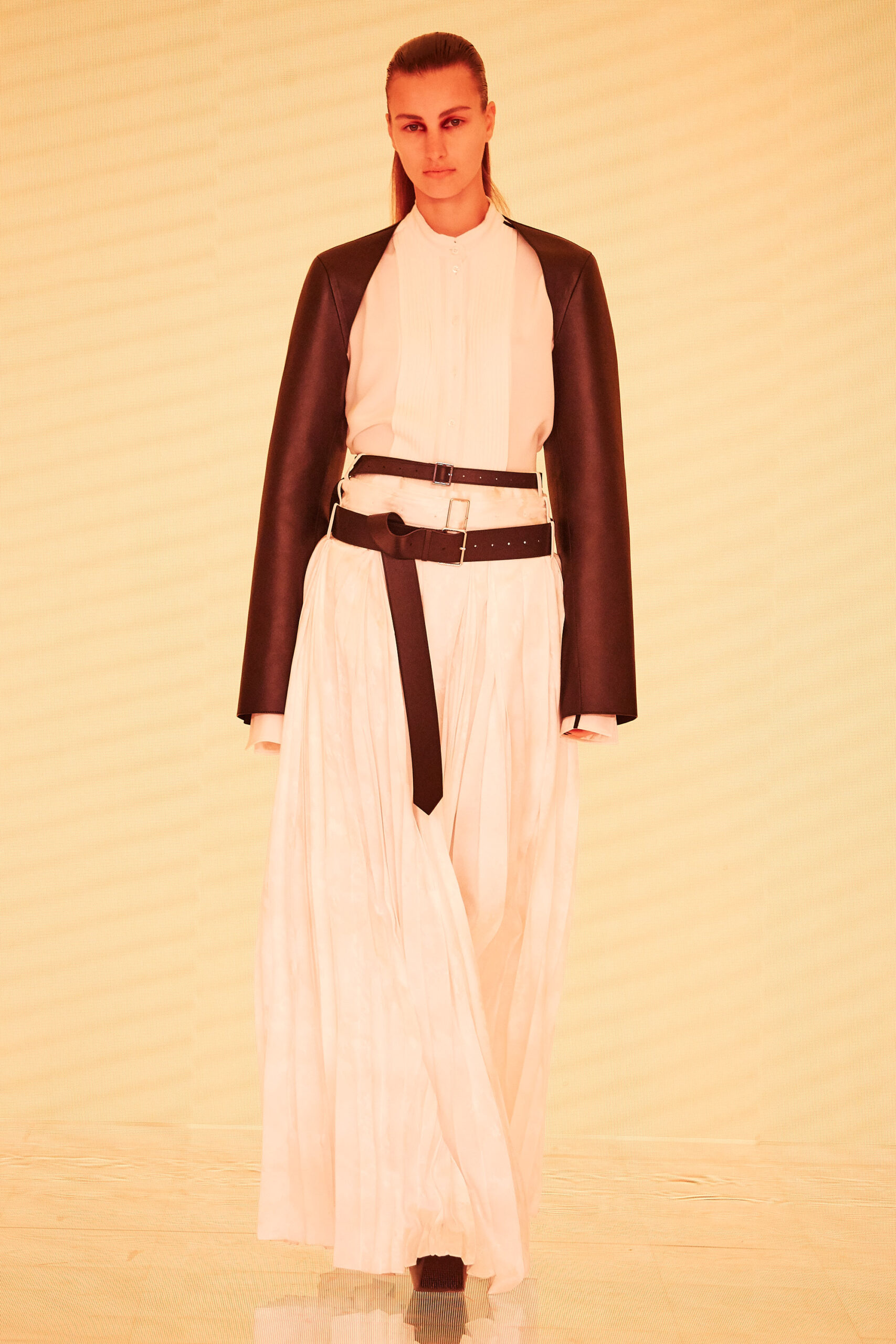

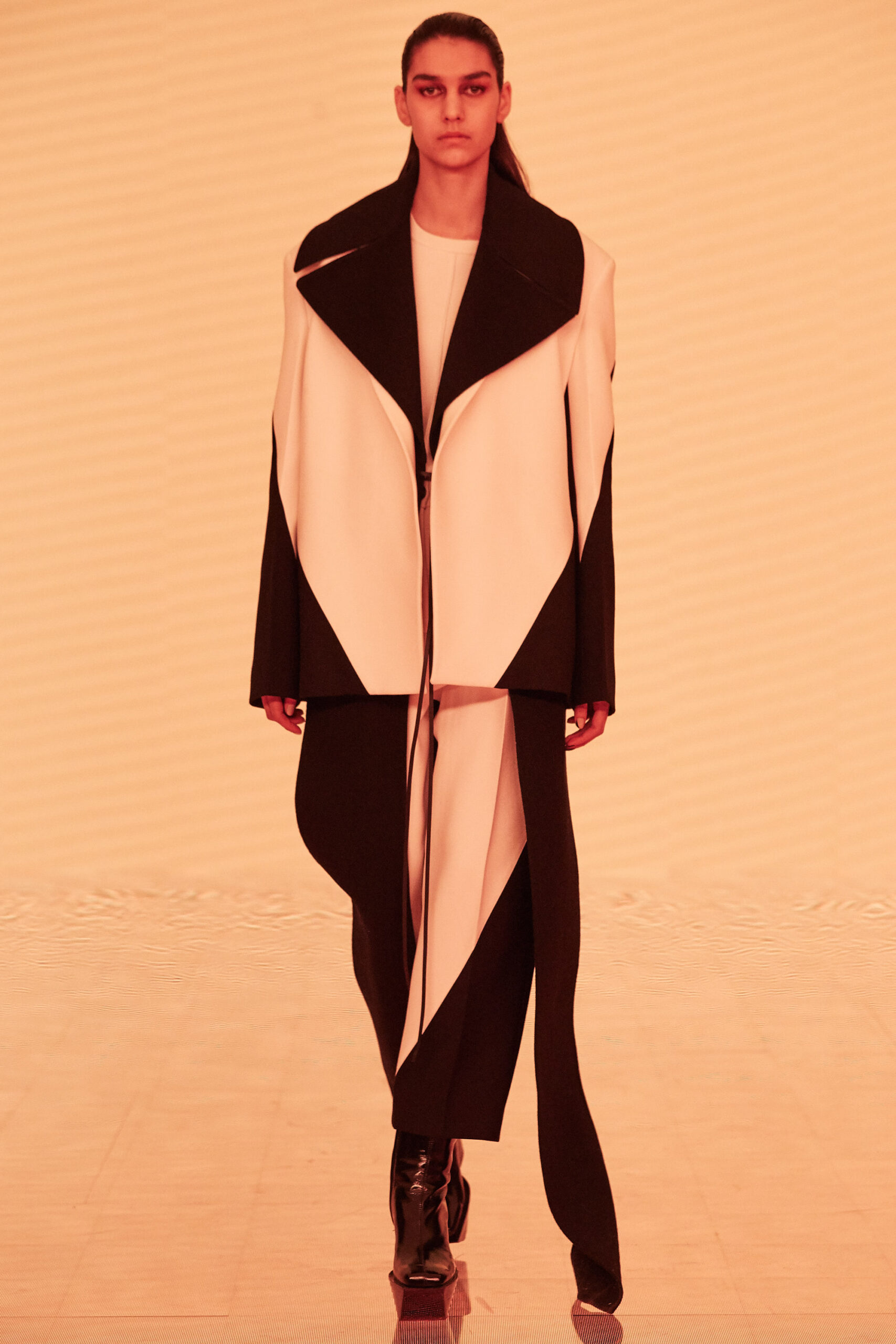

Peter Do does not do ball gowns. Roomy trousers with lots of swagger, yes. Sharp, knife-pleated skirts with irregular hems, yes. Sleek leather shifts with pockets, yes!

But when Instagram’s director of fashion partnerships Eva Chen asked the New York City–based designer to create her ensemble for the Met Gala—the ritzy benefit for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute held each May—he couldn’t refuse.

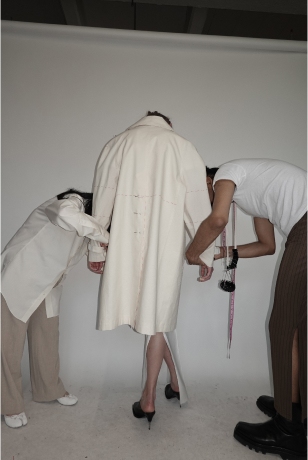

Do and his team came up with a floor-length, cream-colored silk jacket with a dramatic train. Chen wore it over a short strapless dress and one of the brand’s signature asymmetrical wraparound pleated skirts. The jacket-gown had pockets, and the train—per Chen’s Instagram—had “three hidden finger loops sewn into it so I could navigate easily.”

“The end goal for me is always [to create] something that is useful and functional,” Do says of his designs, from his expertly tailored jackets to his more fanciful see-through blouses with ties and slits. “It has to be grounded in some sort of reality: Can you wear it more than once? Does it have pockets? Those are the questions I’ve been interested in since my student days.”

When Chen posted the result on Instagram, she extolled Do’s sartorial pragmatism. “We love a practical designer king,” she wrote.

Practical designer kings (and queens) used to rule New York fashion: Halston and his simple Ultrasuede or jersey dresses, Calvin Klein and his cool minimalism, Donna Karan and her ingenious mix-and-match “seven easy pieces” wardrobe. Yet in the past couple of decades, they’ve pretty much disappeared. American fashion had either gotten fussier (arty experiments, couture-worthy dress-up clothes) or sloppier (streetwear, sweats).

“I’ve been thinking about what it means to be an American designer lately,” Do says. “I think it’s that ability to take things from other places and make them comfortable and functional, but I think we’ve gone too far. It’s maybe too comfortable!”

That’s why Do’s label—elegant, adult, and polished, with a bit of an edge—has struck a chord. After stints at Celine, in Paris, and Derek Lam, he started the label with four friends in 2018. Last year, New York magazine crowned him “the next great American designer.”

Christopher Uvenio, an FIT fashion professor who had Do for his AAS portfolio class, agrees with that pronouncement. Uvenio says, “Do is the Halston of the next generation.”

Do was born in Biên Hòa, Vietnam, and moved to Philadelphia with his family when he was 14. At his new high school, his American classmates made fun of his out-of-date hand-me-downs, and he quickly saw clothes as a way to assimilate and “survive,” adopting an anonymous style.

“I noticed that the moment you change up how you dress, you can pretend to blend into society,” he says. “It was my coping mechanism.”

Do first became interested in fashion through his high school art club. Project Runway was growing in popularity, and Do thought the club could stage a fashion show with clothes made of discarded materials to promote sustainability. His mother bought him a sewing machine for $20 at Kmart, and Do taught himself how to sew dresses out of napkins and trash bags.

“No one would wear the stuff I made,” Do says of those experiments. “But it made me realize that I really loved making clothes.”

He initially enrolled at Brooklyn’s Pratt Institute—“I was really intimidated by Manhattan,” he confesses—but he got frustrated by all the theory classes the first year. “We weren’t making clothes; we weren’t draping,” he says. When he decided to switch to FIT, friends warned him that it was a “technical” school. “I was like, that sounds great!” Do says with a laugh.

His first year at FIT was really tough, he says. “You’re sewing all the time. There are so many projects, so many different types of techniques and constructions. It was almost like boot camp.” Still, Do progressed quickly. His hunger for knowledge and feedback prompted him to create a Tumblr account, where he began posting process photos of his designs for class, and eventually amassed 50,000 followers.

“I knew from the day he walked into the classroom that he was a star in the making,” Uvenio says. One assignment required 10 to 20 thumbnail sketches for a collection; Do came back with 40—all beautifully rendered. “He took his work very seriously. His portfolio was so beautiful and well-researched it could have been a coffee table book.”

Do’s aesthetic was already sleek, sophisticated, and modern: white vinyl raincoats and hand-painted jackets worn with severe black turtlenecks. As a student, he won a CFDA scholarship, a critic award for his senior thesis collection—for which he whipped up an astonishing 20 looks—and the inaugural LVMH Graduates Prize, a major honor that landed him a job at Celine, in Paris.

As much as Do learned from Celine director Phoebe Philo and, later, the New York designer Derek Lam, he chafed at the lack of creative freedom. “I wanted full control. I didn’t want to work so hard for it to be just a part of someone else’s vision,” Do says, adding that it was particularly hard to have a garment that he poured his heart and soul into dismissed or passed over. “It was a really difficult experience. I just wanted to be free, completely free, to do what I want.”

On nights and weekends, he and four friends—including fellow FIT grads Jessica Wu, Advertising and Marketing Communications ’16, Fashion Merchandising Management ’14, who styled Do’s senior thesis collection; and his longtime roommate Lydia Sukato, Fashion Design ’14—hatched a plan for their own fashion brand. (Do met his other two collaborators, Vincent Ho and An Nguyen, through Tumblr.) The five founders—all Asian American—share ownership of the business, which is run as a collective. Wu handles press, Sukato is the operations manager, Ho is CEO, and Nguyen is the image director.

“To build a brand or company, you need more than one person,” Do explains when asked about the “collective” business model. “I feel like for so long, there’s this narrative in fashion that a designer starts a brand [by themselves] and then it just happens. But I know this would never happen if there wasn’t a team behind me.”

In February 2018, they launched a line of T-shirts; by June, they showed a full collection to buyers in Paris.

“We were a bunch of kids—we were so naive,” Do recalls from that trip. “We didn’t understand how these things worked. We just figured everyone would be in Paris [for fashion week] and that we would just go there.” They got cheap plane tickets, rented an Airbnb, and showed up with no appointments. When their fit model couldn’t get into France, press agent Wu donned the clothes. Amazingly, Net-a-Porter, who had seen Do’s clothes on Instagram, bought the entire collection. “We honestly just got lucky that it all worked out!”

Nearly four years later, Do’s star is still rising. Beyoncé, Solange, and Zendaya have worn his clothes, and First Lady Jill Biden’s office has asked for pieces. In 2021, he made his New York Fashion Week debut; that November, the CFDA nominated him for Womenswear Designer of the Year.

Do loves that people want to wear his designs but dreads the attention that comes with such success. He actively avoids the limelight. In photos, he obscures his face by wearing a balaclava, putting his hands out in front of him, or merely looking away from the camera. He often brings team members to press interviews. At the 2022 Met Gala, while he dressed Eva Chen and K-pop star Johnny Suh, Do walked the red carpet in a mask and shades (and a chic deconstructed suit).

“I feel like I expose myself so much with the brand that I want to keep something for myself,” he explains. “I want to have something that’s private, that only the people who know me know. Though I don’t know how long I can keep [that] going.”

After all, Do—who loves clothes so much he even designs in his dreams and will sometimes create those garments when he wakes—plans on staying relevant for many years. His label continues to evolve. He has not wavered from his initial tailored, grown-up aesthetic; his four-piece suit, which includes a jacket, vest, skirt, and pants that can be worn in various combinations, remains a perennial hit. But lately he has loosened up. His fall 2022 collection featured snuggly sweaters and capes (in a soft, washable wool) and ripped, wide-legged jeans.

“When I first started out, I felt like I had a lot to prove, and things were really structured,” Do says. “But now, I feel like people know us for our tailoring, so I’m getting softer. I’m exploring a different side of strength.”

He has a growing number of custom clients—particularly men who want versions of Do’s women’s wear that will fit them—and hopes to have some kind of physical presence in New York, a store or hangout for fans.

“I want to meet the people who wear the clothes—I’m interested in their stories,” Do says. “And I want to know, ‘Is this too much? Why don’t you want to wear this? What do you need?’ That way, I’m making clothes that people actually need and not clothes that I just assume they need.”